Molar Pregnancy: Diagnosis of Hydatidiform Mole Using Bedside Emergency Ultrasound

Case:

A 41-year-old G1P0 female at 7 weeks gestation presents to the emergency department (ED) with 3 days of mild lower abdominal cramping and intermittent vaginal spotting. Nothing makes the cramps better or worse and the spotting randomly occurs throughout the day. She rates the cramping at a 7/10 and describes it as “bad period cramps.” She has no other symptoms and is nervous that “something is wrong with the baby.”

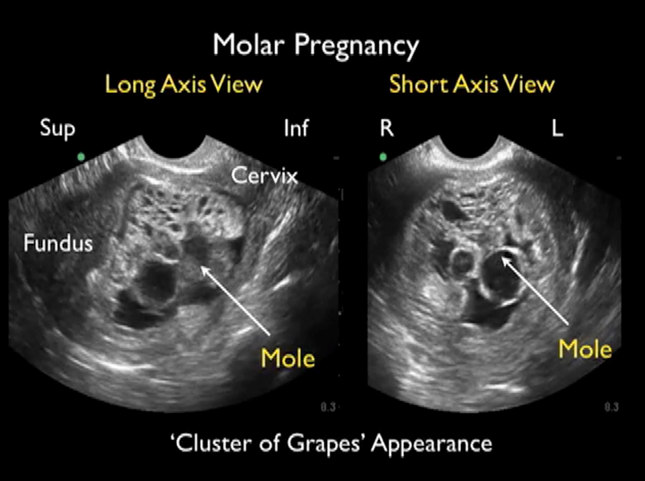

Her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam reveals a well-appearing female with no abnormalities and a non-peritoneal abdomen. Speculum and bimanual exams show a normal, closed cervix without bleeding or discharge. There is no adnexal or uterine tenderness. Results of a serum beta-HCG test are elevated at 148,678. A bedside emergency ultrasound shows a uterus with a snowstorm appearance and multiple grape-like clusters.[1]

Image 1. Short and long axis view of hydatidiform mole (transvaginal ultrasound).

Abdi A, Stacy S, Mailhot T, Perera P. Ultrasound detection of a molar pregnancy in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(2):121-122. doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.7.12994

Diagnosis:

Hydatidiform Mole

Discussion:

Hydatidiform moles, commonly referred to as molar pregnancies, represent abnormal trophoblastic proliferation originating from the placenta resulting in a non-viable pregnancy.[2] The pathogenesis of hydatidiform moles most likely stems from excess paternal genome due to loss of maternal haploid genome in the ovum (Figure 1). This can present as a complete (46 XX or XY without fetal tissue) vs. partial (69 XXX or XXY containing fetal tissue) molar pregnancy. The outcome of either genetic event is villous hydrops and non-malignant trophoblastic tissue proliferation.[1] It is important to note that complete hydatidiform mole is associated with the development of gestational choriocarcinoma.

Hydatidiform moles tend to spontaneously occur at extremes of reproductive age and are exceedingly rare. In North America, the incidence is 0.5-1.84 in 1,000 pregnancies; however, in Southeast Asia the incidence is as high as 13 in 1,000 pregnancies.[3] Vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom in molar pregnancy and the diagnosis can be confirmed with serum beta-HCG levels above 100,000 mlU/mL as well as with bedside emergency ultrasound showing a “snowstorm appearance” with grape-like structures representing a vesicular intrauterine mass containing cysts.[1]

Case Resolution:

Management of patients with hydatidiform mole includes chest radiograph, complete blood count, liver panel, thyroid function tests, coagulation studies, blood type, and urinalysis.[4] Chest radiograph peri- and post-operatively can help evaluate for trophoblastic emboli in the pulmonary arterioles. Suction curettage is the method of evacuation for molar pregnancies; however, in patients who do not wish to reproduce in the future, hysterectomy is associated with a reduced rate of malignant sequelae.[4] This patient was admitted and received emergent suction dilatation and curettage. The operative report found cystic heterogeneous sanguineous material consistent with molar pregnancy and the pathology report confirmed villi with histological features suggestive of complete hydatidiform mole.[1]

Take-Aways:

The most common presenting symptom in molar pregnancy is first trimester bleeding

The diagnosis of molar pregnancy is made with an elevated beta-HCG above 100,000 and an ultrasound showing grape-like structures in the uterus.

Management of molar pregnancy includes dilation and curettage with hysterectomy being the definitive treatment to prevent future risk of choriocarcinoma in patients with complete hydatidiform mole.

AUTHOR: Meggie Cook, MS4 at Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

FACULTY REVIEWER: Kristin Dwyer, MD

References

Abdi A, Stacy S, Mailhot T, Perera P. Ultrasound detection of a molar pregnancy in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(2):121-122. doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.7.12994

Hui P, Buza N, Murphy KM, Ronnett BM. Hydatidiform Moles: Genetic Basis and Precision Diagnosis. Annual review of pathology. 2017;12:449-485.

Wei P-Y, Ouyang P-C. Trophoblastic diseases in Taiwan: A review of 157 cases in a 10 year period. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1963/04/01/ 1963;85(7):844-849. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(16)35584-3

Hurteau JA. Gestational trophoblastic disease: management of hydatidiform mole. Clin Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2003;46(3):557-69. doi:10.1097/00003081-200309000-00007