Yes, Officer: Law Enforcement and the Emergency Department

Emergency department providers are no strangers to the presence of law enforcement officers (LEOs) through the course of their job duties; they are integral to public safety and often hospital safety, conduct criminal investigations, and assist in pre-hospital care. Despite the frequency of law enforcement in U.S. emergency departments, interactions with providers and staff often presents unique challenges. When faced with a patient needing both medical care and involvement of law enforcement, ED providers can face several conflicts of interest: providers can feel compelled to help law enforcement in an investigation by disclosing details or health information to maintain a healthy working relationship; unfortunately, this also directly conflicts with protection of privacy, forming a patient-provider alliance, and can spark fear of medico-legal implications.

To help provide a better understanding of basic law enforcement structure, the judicial process, and to address common concerns between law enforcement and the emergency department in our hospital system, a panel of local experts was convened at our weekly residency conference for joint-discussion. Using several sample cases as a framework for dialogue, representatives from local law enforcement, hospital security, the Department of Corrections, the Attorney General’s Office, hospital legal counsel, and Risk Management were present to provide insight, expert opinion, and answer specific questions.

In Part One of this series, we will discuss some law enforcement and judicial process basics, as well as discuss the common scenario of the intoxicated driver in the emergency department. In Part Two, we will discuss some more detailed situations, including navigating investigation and care of patients in extremis.

Below each case is a summary of important points and questions raised with our experts, based upon the scenario at hand. It is important to note, that responses below may vary based upon specific circumstances, local/state laws, and hospital policy. The information provided is merely for general educational purposes, and should not be used as formal legal guidance; should you have specific questions, please consult your appropriate risk management official or legal counsel.

Case 1: A 21-year-old presents with police for a hand injury – The Basics

While Rhode Island presents some unique characteristics due to its overall small size, understanding what facets of law enforcement are present in a particular area are important as to what to expect in the emergency department. As a tertiary care center, Rhode Island Hospital frequently sees patients presenting with local or state law enforcement agencies, state sheriffs, and corrections officers; however, other agencies such as federal law enforcement (U.S. Marshals, Federal Bureau of Investigation, etc.) and military police are also active. When entering the room of a patient with a law enforcement officer present, several key points should be considered:

Custody or Not? - From the beginning of the encounter, providers should ascertain whether the patient is in police custody or not. Although ED providers will not alter the patient’s judicial course, this distinction can alter the interaction with law enforcement and help alert the provider to specific considerations about patient disposition.

Patient Privacy Considerations – As with all patients, providers have a duty to uphold patient confidentiality. Although law enforcement providers are responsible for patients in their custody, it is often beneficial to have a discussion with the responsible LEO about performing a confidential history and physical exam, within reason. This benefits by protecting patient privacy, establishing rapport with the patient and showing allegiance to the patient-provider relationship, and allows patients to disclose history they may otherwise be unwilling to share due to fear of criminal retribution. Special attention should be paid to sensitive examinations, such as pelvic exams, if indicated. Unlike providers, LEOs are not required to abide by HIPAA, and this needs to be considered when sharing patient protected health information. It should go without saying, if there are any concerns about safety or security, the LEO should remain at bedside at all times.

Body Cameras – Due to the current environment in law enforcement, more agencies across the country are equipping officers with body cameras. These devices may be worn on chest, shoulder, or eyeglasses, and are only recording when activated by the officer in performance of law enforcement related activities. As of this writing, most agencies in our state are not routinely using body cameras, although this practice is currently in flux. Unless an interaction is specifically related to a law enforcement action, such as recording a legal blood draw, body cameras should not be used during patient interactions, and providers can cite privacy concerns. The ACEP Clinical Policy: Law Enforcement Information Gathering in the Emergency Department can also be used for reference and support.[4]

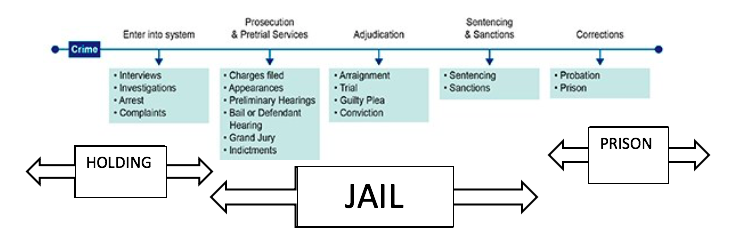

Disposition – Providers need to take extra consideration of a patient’s course in the judicial process when determining a safe disposition plan. Unlike jail and prison facilities, patients in custody of law enforcement and being held at a police station holding area will have minimal, if any, access to medical care. This also can affect even simple disposition plans: we raised the case of a patient in custody with a simple cellulitis amenable to oral antibiotics. Under normal circumstances, a discharge with oral antibiotics would be appropriate; however, if the patient is planned for even a day in a holding cell, providers should consider potential observation admission, as LEOs may be unable to obtain a prescription (for example, at an outpatient pharmacy), and do not have medical staff on hand to administer this treatment while being held. Below is a figure modified from the Federal Bureau of Investigation Criminal Process Overview showing steps in the criminal process and expected disposition[5]:

Overview of the criminal process

Case 2: 27-year-old presents after a motor vehicle accident and suspicion of Driving Under the Influence (DUI) – It’s Complicated

Intoxicated drivers involved in motor vehicle accidents remain a significant problem in the United States, with more than 10,000 people annually losing their lives as a result of driving under the influence[1]. Emergency department providers are often at the forefront of caring for patients in the aftermath of these incidents, often times patients in custody responsible for incidents. As with any patient with traumatic injuries, the priority should be a systematic evaluation to exclude life threatening injuries.

Initial Investigation – A DUI investigation begins in the field with officers conducting standardized field sobriety testing (SFSTs), a series of steps often viewed on law enforcement television shows. When testing is abnormal, this is often followed by preliminary alcohol breath test; however, in some instances, this testing cannot be performed, secondary to significant impairment, concurrent injuries, or refusal by a subject to perform the test. In these cases, patients may present to the ED with law enforcement for definitive testing via a blood draw.

Legal Blood Draws – The request for a legal blood draw by law enforcement can be fraught with apprehension due to concerns about the steps of consent, and possible medico-legal ramifications. This very concern was brought to national attention in 2017 when a Utah nurse was arrested for refusing to draw blood from an unconscious patient.[6] In our state, patients in custody for suspicion of DUI may consent to a legal blood draw, or the law enforcement officer must produce a search warrant. Emergency department nurses are often at the forefront of this process, as persons in custody will not see a licensed independent provider unless specifically requested for another reason, such as concern for concurrent injuries. In some states such as New York, this process may be fulfilled in the pre-hospital environment by advanced EMTs or paramedics.[7] If applicable, providers should be familiar with the appropriate protocols and procedure, as online medical direction may be needed in these instances when questions of legality or capacity for consent arise. In the ED setting, providers should be familiar with hospital policies and applicable laws surrounding this, as nursing staff may also rely upon providers for guidance.

Case 3: 18-year-old critically injured from a gunshot wound – Can I have that shirt?

Emergency departments across the country frequently care for victims of violent crime, especially in urban areas or regional trauma centers. Patients may be innocent victims, suspects, or already in police custody on presentation. Providers are often required to report incidents of violent crime (particularly firearm violence) to the local police, triggering an investigation. The presence of law enforcement during trauma resuscitation is specifically addressed by the trauma handbook issued by Rhode Island Hospital’s Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, and serves as our “bible” for managing trauma patients.[10]

Patient Care – Resuscitation and stabilization of the trauma patient should supersede law enforcement investigation. While patient care is paramount, ED providers and staff should be cognizant of the investigation, and can take small steps during resuscitation to help preserve evidence: for example, when cutting off clothing from a patient with a gunshot wound, care should be taken to avoid cutting through the clothing defect. When the life threats to the patient are stabilized, providers should be considerate of the formal investigation, particularly if there is a threat to others or the general public (such as a terrorist act), and information is time-sensitive.

Chain of Custody – Maintaining the integrity of evidence when possible can be vital to the judicial process if charges are filed in a criminal investigation. To support law enforcement, potential evidence should be appropriately collected and documented using a chain of custody form. Paper evidence collection bags are present in the trauma bays at our facility, and steps are taken to encourage potential evidence collected during a violent crime is placed in appropriate containers. Patient belongings can be integral to an investigation and often overlooked in the chaos of a resuscitation. It is also important to know that belongings collected during a resuscitation should be protected; in our facility, belongings can only be released to law enforcement with patient/representative permission, or with a valid search warrant.

Release of Information – LEOs investigating an incident, whether a patient is in custody or not, will often have general questions such as confirmation of an identity or overall patient status. Noting the concerns of patient privacy discussed in Part One, it is reasonable to provide general information to law enforcement about a particular patient’s condition without need to disclose protected health information. Confirmation of an identity may be beneficial as LEOs can sometimes obtain contact information and make family notification. Often times informing law enforcement that a patient cannot be questioned, such as if intubated, can help relieve initial concerns of conflict of patient care and investigation steps.

Case 4: 55-year-old inmate presents for chest pain evaluation – Decisions, Decisions…

It is well known to the medical community that incarcerated patients are vulnerable, and frequently have higher rates of chronic medical illness and poorer health outcomes.[9] Although medical care is available at many facilities, inmates may be brought to the emergency department for a number of reasons. As noted in Part One, recognizing this vulnerable population and considering incarceration location must be considered when choosing a disposition for these patients. Some inmates may be seeking secondary gain by presenting to the ED, but this remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

HEART Score? – Extra caution needs to be taken in incarcerated patients as above. Typical modalities used in the ED, such as clinical decision instruments, need to be used with caution, as these often do not explicitly consider high risk patients such as those in prison.[4] When considering discharge of incarcerated patients, many facilities have medical staff available on site; for example, our unified state correctional facility does have the ability to provide medical care and perform basic diagnostic testing, such as X-rays. Despite this, if there is clinical concern about a patient, often the safest disposition is for admission. If planning discharge, providers should also be aware of a specific process in providing discharge instructions and follow up; correctional officers often deliberately withhold information about outpatient follow up (such as appointment dates, times, and location) from inmates for security purposes. In our institution, follow up materials are often returned in a sealed envelope to the accompanying corrections officers to be handled by jail/prison medical staff upon return of the inmate.

Decision Making Capacity – While incarcerated, inmates do retain decision making capacity for healthcare and should be encouraged to participate in this decision making process. Although we briefly discussed this concept, the complexity and intricacies of inmate decision making capacity in cases of end-of-life or other similar situations is beyond the scope of this post.

Summary and Take Home Points

The clinical environment of emergency medicine will inevitably bring ED providers/staff, law enforcement officers, and those in the judicial process together under one roof. Providers should recognize and understand the complexities of these interactions, while maintaining support for patients and a working relationship with law enforcement/correctional officers. After our meeting with key stakeholders, we received universally positive feedback from providers and law enforcement representatives alike. In general, being open and honest with all stakeholders in an interaction can have a positive outcome and help identify potential difficult scenarios. As noted above, if there are ever concerns about a potential situation, hospital risk management is always available and willing to assist in the navigation of these encounters.

Please feel free to post additional thoughts, comments, or questions about this topic in the thread below!

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the representatives from the City of Providence Department of Public Safety, Rhode Island Office of the Attorney General, Rhode Island Department of Corrections, and several Lifespan offices, including legal counsel, Risk Management, and Security, as our panel would not have been possible without their time and expertise. In honor of National Police Week, we would also like to extend a special thanks to the men and women across the country working in law enforcement and corrections for their dedication and sacrifice each and every day.

Faculty Reviewer: Dr. Alexis Lawrence

References and Additional Resources for Review

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, “Risky Driving”, accessed at: https://www.nhtsa.gov/risky-driving/drunk-driving

Tahouni M, Liscord E, Mowafi, H; “Managing Law Enforcement Presence in the Emergency Department: Highlighting the Need for New Policy Recommendations”, Journal of Emergency Medicine, Volume 49, Issue 4, October 2015

Valdovinos E, Siroker H, Shoenberger J; “Interactions with Law Enforcement in the ED”, Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives, October 2019, accessed at: https://www.emrap.org/episode/emrap20196/interactions

Swadron S and Eiting E; “Patients in Custody”, Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives, April 2019, accessed at: https://www.emrap.org/episode/emrap2019april/patientsin

American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policy: “Law Enforcement Information Gathering in the Emergency Department”, Approved September 2003 and revised June 2017, accessed at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/law-enforcement-information-gathering-in-the-emergency-department/

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Victim Services: “Overview of the Criminal Process” original webpage figure, accessed at: https://www.fbi.gov/resources/victim-services/a-brief-description-of-the-federal-criminal-justice-process#The-Trial

Wamsley, L: “Utah Nurse Arrested for Doing Her Job Reaches $500,000 Settlement”, National Public Radio, November 2017, accessed at: https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/11/01/561337106/utah-nurse-arrested-for-doing-her-job-reaches-500-000-settlement

New York State Department of Health, Bureau of EMS Policy Statement 11-01, released January 4th, 2011 and accessed at: https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/ems/policy/11-01.htm

Tobey, M and Simon, L; “Who should make decisions for underrepresented patients who are incarcerated?”, AMA Journal of Ethics, Vol 21 No. 7, July 2019

Rhode Island Hospital, Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, Trauma Handbook, Published 2017