Rounding Out A Case of Acute Pancreatitis

CASE

An otherwise healthy 6 year-old female presented with lower abdominal pain and non-bloody, non-bilious emesis since 11:00 PM the previous night. Several hours prior to the onset of her symptoms, she was playfully thrown into a pond where she was swimming. She subsequently had take-out brown rice and vegetables with her family. Nobody else developed symptoms. Her pain was worse with ambulation and bumps in the road. She has had no diarrhea, constipation, fevers, urinary symptoms, or other acute complaints. She had similar but less severe episodes of these symptoms in the past. The patient’s father had a history of a “blood disorder” requiring abdominal surgery.

Vitals were within normal limits. The patient was uncomfortable but non-toxic appearing and was tender to palpation of the lower abdomen. Voluntary guarding was noted without rebound or rigidity. Her exam was otherwise reassuring.

The complete blood count was notable for a hemoglobin of 13.2 g/dL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) of 37 g/dL (elevated), red blood cell distribution width (RDW) of 18.8% (elevated), and 1+ spherocytes on peripheral smear. The remainder of her labs were notable for a lipase of 5983 U/L, Total Bilirubin of 6.5 mg/dL (Direct 1.4, Indirect 5.1), AST of 441 U/L, and ALT of 475 U/L.

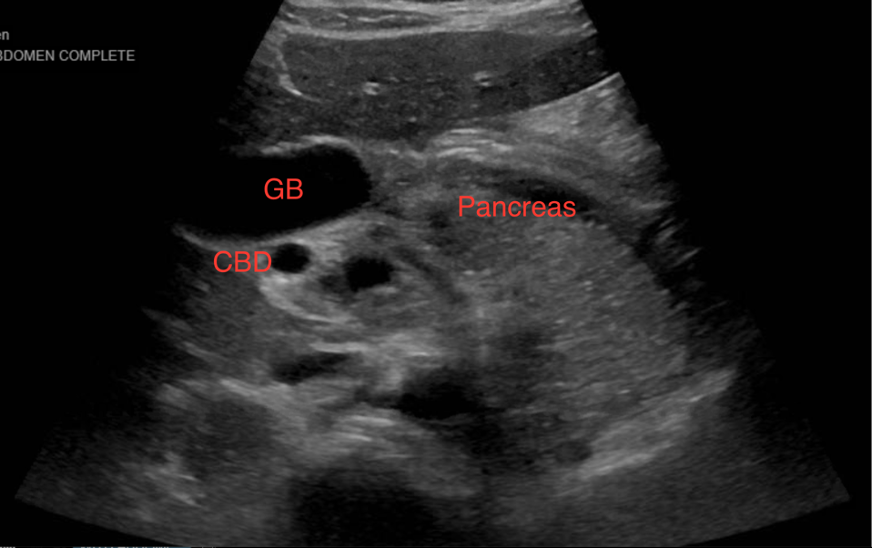

Abdominal ultrasound showed an enlarged and echogenic pancreas as well as intra and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with common bile duct (CBD) measuring 6 mm. The gallbladder was mildly distended without definite calculi or sludge. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Abdominal ultrasound showing pancreatitis.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was subsequently obtained and showed an edematous and enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic inflammatory stranding and diffuse peripancreatic fluid throughout the retroperitoneum. The CBD measured up to 4mm. The gallbladder was normal.

DIAGNOSIS

Acute pancreatitis thought to be secondary to gallstones in the setting of previously undiagnosed hereditary spherocytosis

DISCUSSION

Acute pancreatitis

In recent decades, the incidence of acute pancreatitis (AP) in the pediatric population has been increasing, though it is unclear how much of this is due to a higher prevalence as opposed to more thorough evaluations. [1] As much of the literature on acute pancreatitis has historically been focused on adults, the diagnostic criteria and management of the pediatric population are likely already familiar to emergency medicine providers. Patients are diagnosed with acute pancreatitis if they meet at least two of three diagnostic criteria: abdominal pain, serum lipase or amylase levels at least three times above normal, and imaging findings compatible with the diagnosis. Though CT imaging of the abdomen with contrast is considered the diagnostic gold standard in adults, ultrasonography and MRI are often used with children to aid in the diagnosis while minimizing radiation exposure. [2] Children, like adults, are unlikely to present with a textbook case of epigastric abdominal pain radiating to the back, so it is important to keep AP on the differential and to look out for less obvious symptoms such as back pain alone, irritability, and lethargy. [3] Management focuses on supportive care by slowly advancing the patient’s diet, treating with intravenous fluids, anti-emetics, and analgesics, and monitoring for signs of complications such as fluid collections or multi-organ disease. [4]

In AP, an important divergence between the adult and pediatric populations is the differential diagnosis. Whereas in adults one typically expects biliary disease or alcohol use to be the cause, in kids this is not the case. Alcohol is a very rare underlying etiology in children. Biliary disease is also less likely, but is actually more common than previously thought. [4] The patient in this case, for instance, may have developed pigmented gallstones due to hemolysis in the setting of hereditary spherocytosis. Other possible etiologies include medications such as valproic acid, azothioprine, and mercaptopurine, systemic diseases such as Kawasaki disease or Lupus, autoimmune diseases, infections, and metabolic disorders. [3] Anatomic abnormalities such as choledocal cysts or annular pancreas are more likely to cause AP earlier in life. Finally, genetic causes of pancreatitis such as mutations in the genes PRSS-1 and SPINK-1, which are both involved in regulating pancreatic enzymes, are likely to cause multiple distinct episodes of pancreatitis without irreversible damage to the pancreas, termed Acute Recurrent Pancreatitis. [4]

Hereditary spherocytosis

Hereditary Spherocytosis (HS), as the name suggests, is typically inherited. 75% of cases are passed down in an autosomal dominant fashion, though autosomal recessive inheritance and de novo cases occur as well. [5] The underlying issue is a variety of possible defects in the red blood cell membrane, leading to progressive membrane loss with a reduced surface area to volume ratio, thus leading to poor deformability and an increased proclivity for hemolysis, especially when passing through the spleen. [6] Patients can present at any age and symptoms range from nonexistent to severe depending on the inherited defect and the level of penetrance. [5] In neonates, HS can present as hyperbilirubinemia causing jaundice. In older children and adults, the diagnosis can be made incidentally based on bloodwork or in patients with symptomatic anemia, splenomegaly, aplastic crisis, or biliary disease. [7] Bloodwork suggestive of HS includes anemia with elevated MCHC and RDW, spherocytes on a peripheral smear (Figure 2), and an elevated reticulocyte count. While the above results in combination with a known family history and negative Coombs testing to rule out immune-mediated hemolysis strongly suggests the diagnosis, confirmatory tests, such as osmotic fragility testing and flow cytometry evaluation, are available as well. [6] In terms of management, patients with mild disease may just require monitoring, while in moderate to severe cases, options include folate supplementation, partial or total splenectomy, and blood transfusions. [8]

Figure 2. Representative smear showing spherocytes. [9]

CASE RESOLUTION

The patient was admitted overnight and treated symptomatically. She was then discharged home for follow up with gastroenterology for repeat bloodwork and imaging as well as for follow up with hematology to have confirmatory testing for hereditary spherocytosis.

TAKE-AWAYS

Pancreatitis is not just an adult disease!

Avoid anchoring on a differential diagnosis based on the reported area of abdominal pain.

Family history can be crucial.

Sometimes zebras from board exams will pop up in real life.

AUTHORS

Sean Reid, MD is a second year emergency medicine resident at Brown University

Meghan Beucher, MD is an Assistant Professor in emergency medicine at Brown University

REFERENCES

Randall M, McDaniels S, Kyle K, Michael M, Giacopizzi J, Brown L. Pancreatitis In Pre-Adolescent Children: A 10 Year Experience In The Pediatric Emergency Department. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2019;19(1).

Abu-El-Haija M, Kumar S, Quiros, J, Blakakrishnan K, Barth B, Bitton S, et al. The Management of Acute Pancreatitis in the Pediatric Population: A Clinical Report from the NASPGHAN Pancreas Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(1):159-176.

Suzuki M, Kan Sai J, Shimizu T. Acute Pancreatitis in Children and Adolescents. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5(4):416-426.

Srinath A, Lowr M. Pediatric Pancreatitis. Pediatrics in Review. 2013;34(2):79-90.

Narla J, Mohandas N. Red Cell Membrane Disorders. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018;39:47-52.

Ciepiela O. Old And New Insights Into the Diagnosis of Hereditary Spherocytosis. Ann Transl Med. 2018; 6(17): 339-349.

Manciu S, Matei E, Trandafir B. Hereditary Spherocytosis- Diagnosis, Surgical Treatment and Outcomes. A Literature Review. Chirurgia. 2019; 112(2):10-116.

Zamora A, Schaefer C. Hereditary Spherocytosis. Stat Pearls. 2019.

ASH Image Bank [Internet]. American Society of Hematology. Spherocytes-herediatry spherocytosis. 2016[accessed 2020 August 7]. Available from: https://imagebank.hematology.org/image/60308/spherocytes--hereditary-spherocytosis?type=atlas#:~:text=Published%20Date%3A%2001%2F13%2F,cells%20and%20lack%20central%20pallor

![Figure 2. Representative smear showing spherocytes. [9]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56e8a86a746fb97ea9d14740/1598635288175-TUXUMNNWY4GCCO4ZFP9J/Picture2.png)