The History of Resuscitation

Early Resuscitative Efforts

Since the dawn of humanity, medical procedures have been used and are one of our species’ defining characteristics. One such example is the jaw bone of a Neolithic individual from 13,000 years ago, which was found to have cavities drilled and filled in a manner not unlike the modern technique. [1] Various procedures and tinctures were used to ameliorate a wide range of pains and suffering, so it is no wonder that early medicine was also applied to resuscitating the dead.

Photo 1: Prehistoric Dentisty

The first written reference to a resuscitative effort can be found in Mayan hieroglyphs from around 4,000 years ago that show the use of rectal fumigation, or insufflation of the rectum with air, smoke, or medication. [2] About 2,400 years ago, both the Old Testament of the Bible and the Babylonian Talmud referenced mouth-to-mouth resuscitation of children. Many other texts contain loose descriptions of early resuscitation techniques but are often lacking in detail, and certainly in understanding of underlying pathophysiology.

Photo 2: Mayan enema

A more uniform approach to resuscitating the dead came in Europe, where between 500 and 1500 AD the standard of care involved two steps - warming the patient, and stimulating them in some form. This came from an understanding that a dead body becomes cold and motionless, so the opposites must surely bring back their life essence. As such, hot coals were placed on the corpse and hot teas poured down their throat. As for stimulation, this was often performed through flagellation, whipping, or other intense rituals such as the use of stinging nettles. [3]

In the 1600s, Thomas Sydenham suggested the use of tobacco smoke enemas to add heat and stimulation to the decedent, and this technique was used through the 1800s until better methods emerged. In the case of drowning, which remained the most common identifiable cause of sudden death throughout most of history, both tobacco smoke enemas and hanging individuals upside down were utilized. In the mid-1700s, there was greater awareness about the life-sustaining concept of breathing and thus efforts began to focus on recreating inspiration and expiration, such as rolling the dead over a large barrel, hanging them over the back of a horse which was forced to trot, and repeatedly tightening and loosening a cloth tied around the chest. [3] Needless to say, these techniques were not very successful in resuscitating the dead, though they did lead to the first mass medical education of the general public in 1767 as well as the formation of medical societies that were dedicated to resuscitation and emergency medical care.

Photo 3: Tobacco smoke enema

While the male-dominated western society was busy burning and whipping dead bodies, blowing smoke up their rectums, and trotting them around on the back of horses, a Persian physician in the 1400’s had developed CPR. See his description below.

“If the patient had weak pulse or pulselessness and yellowness, shake him, stimulate and move the arms and the left side of patient and compress the left side of his/her chest." [4]

Moreover, midwives throughout Europe, and presumably throughout the world, used mouth to mouth to resuscitate newborns for hundreds of years before it was then “developed” by male physicians. [5]

Our Understanding of Breath

The development of modern resuscitation efforts was made possible through our understanding of anatomy and physiology. Breath, or “pneuma,” was first understood to have a life-giving quality by Greek philosophers in the 6th century BC, though the gases that made up air and their interactions in the body were not known for over 2,000 years. Robert Boyle, in the mid-1600’s, showed that animals died when placed into a vacuum and through numerous experiments carried out the subsequent centuries, we came to understand the roles of oxygen and carbon dioxide in maintaining life. This was quite conceptual, though, as we did not have a reliable means of assessing the blood gases of our patients until the mid-1950’s, when Dr. Severinghaus invented the first three electrode gas analyzer, which allowed the user to know the patient’s pH, pO2, and pCO2. Not only did this revolutionize our management of patients, it fundamentally changed our understanding of diseases.

Our Understanding of Death

Traditionally, Western medicine has defined death as the cessation of breath and the heart. That view was challenged throughout the years by scattered cases of people who seemingly came back from the dead, such as Anne Greene who was wrongfully convicted of infanticide in 1650. Ms. Green was hanged for thirty minutes and released when she appeared killed; however, much to the surprise of the medical examiner, she was found to be alive the next morning. She ultimately went on to have her sentence overturned, living out the rest of her life. [6] Greene’s case, and others throughout the 17th and 18th centuries added to a growing body of literature that suggested the reversibility of death.

Our conception of death has continued to evolve over time with our resuscitative techniques. In the early 20th century the introduction of mechanical ventilation forced physicians to reconsider the definition of death, if not the cessation of breath. Thus the locus of death shifted to the brain and whether an individual was in an irreversible coma. Our definition of death will evolve as conditions thought to be irreversible today become reversible in the future.

Securing an Airway

The first definitive airway is described in the Rigveda, a Hindu book of medicine written between 2,000 and 1,000 BC. It describes a tracheostomy, which was the mainstay of airway management for over 3,000 years. There is even an Egyptian hieroglyphic from 5,000 years ago that may depict a tracheostomy, though this is debated. Paul of Aeginas described what is effectively the modern tracheostomy in the 7th century.

“In cases of inflammation of the mouth or palate, it is reasonable to use tracheostomy (pharyngostomy) in order to prevent suffocation. We cut the trachea below the upper part at the level of the third or fourth ring. For a better exposure of the trachea, the head needs to be reclined. A transverse incision is made in between two tracheal rings, so it is not the cartilage that is incised, but the tissue in between.”

Photo 4: Laryngotomy

Even though the anatomy was well understood, it was a highly morbid procedure due to a lack of aseptic technique, analgesia, sedation, and cuffed tubes. This is largely why the procedure was denied to one patient GW in 1799, who instead had his bacterial epiglottitis treated with blood letting. Unsurprisingly, it was unsuccessful and George Washington ultimately passed away. [7]

Functioning vocal cords were first visualized indirectly in 1854 by Manuel García, a Spanish vocal pedagogist, using a series of mirrors. This caught the attention of physicians at the time who began to perform orotracheal intubation. However, the first paper describing the procedure touted a success rate of only 2/7, where both patients ultimately required tracheostomy. [8]

Photo 5: Visualization of vocal cords

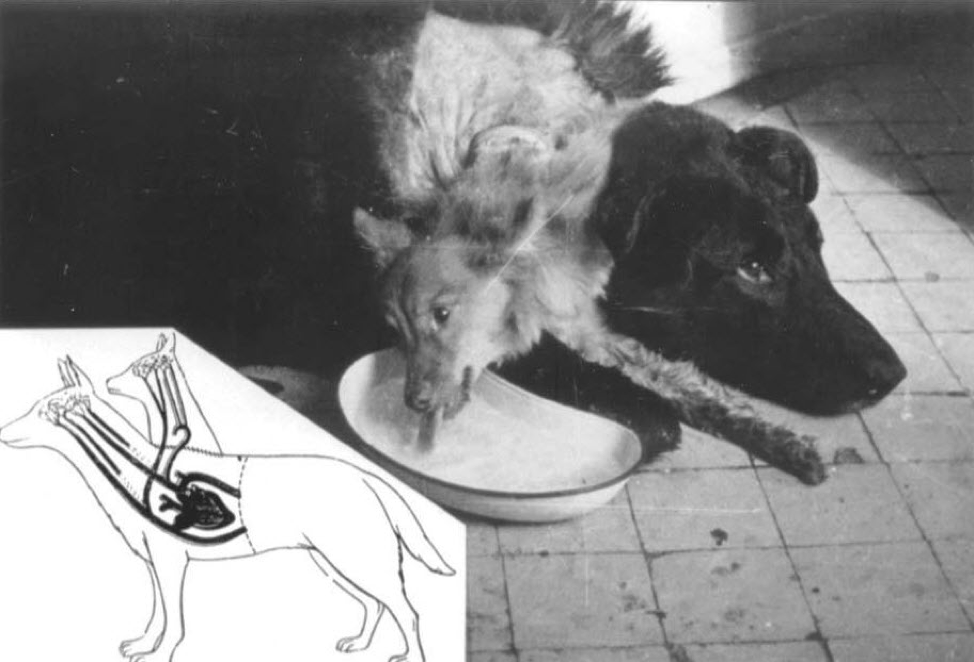

Direct laryngoscopy was invented in 1894, with a variety of iterations on the laryngoscope until Sir Robert Macintosh invented the Mac blade in 1954, which remains essentially unchanged. Successful intubation depends on reliably viewing the vocal cords as well as the endotracheal tube (ETT) itself. Initially most were made of reed or hard metal, and used while the patient was wide awake, and it wasn’t until the advent of soft synthetic materials in the 1930’s that the modern ETT was invented. The device was marketed and popularized by a traveling show in which the inventor’s dog aptly named “Airway” was repeatedly intubated and extubated hundreds of times across the country. [9]

Photo 6: Airway the dog demonstrating intubation.

Defibrillation

Much in the way that this poor dog helped to further airway management, chickens helped us to begin to understand the electrical activity of the heart. The first recorded experiments of the effects of electricity on the body were carried out in 1775 when a scientist noticed that he could render chickens lifeless by delivering a shock. Still, some would also come back to life with a countershock. [10] There was no understanding of ventricular dysrhythmias so the cause of death was unknown. Electrically induced ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia and defibrillation were first described in 1899, though it was not widely accepted until more than thirty years later. [11] This is understandable considering that electrocardiograms weren’t accurate until the early 20th century. The first case of successful defibrillation of a human occurred in 1947, when a cardiothoracic surgeon shocked a fourteen-year-old patient in the operating room by directly applying an electrical current to the patient’s heart, and witnessed cessation of the arrhythmia. [12] For the next decade, it was believed that defibrillation could only be carried out directly on the heart and that transthoracic defibrillation would not be possible.

The Future of Resuscitation

While it is difficult to predict the direction of future resuscitative efforts, prior history sheds light on general trends in resuscitation. Over time, our techniques have become increasingly standardized, with a growing body of research to support certain methods, while disproving others. That being said, data in resuscitation is notoriously difficult to obtain; thus quality and generalizability can be limited. As such, broader and randomized research is needed to guide future standards of resuscitative care.

Specific avenues to improve resuscitation may be through developments in existing technologies such as quicker and safer deployment of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and advances in CPR such as the heads-up method. Much as the Mayans described 4,000 years ago, it appears that enteral ventilation is entirely possible. Scientists have used both gas and liquid in the rectums of mammals to successfully overcome respiratory failure. [13] Transplant science may provide an avenue for resuscitation in cases of extreme bodily or cerebral damage. As early as 1948, full head transplants have been successfully carried out. [14] One may imagine replacing a patient who is “brain-dead” with a working brain as a means of resuscitation, thus further complicating our definition of death. As the field grows, artificial organs may be used in cases of organ failure, whether it be heart, kidney, liver, or another anatomical structure. Cyborg hearts are already being implanted, made of both synthetic materials and bovine pericardium. Moreover, artificial hemoglobin-based blood alternatives have shown promise in animal models, and will likely be used in human subjects in the near future.

Photo 7: Canine head and forepaw transplant expirement

More likely, though, our advances in resuscitation will be through cataclysmic shifts that are impossible to predict, as they have been in the past. Paradigm shifts in the way we think about pathology, anatomy, and death have led to dramatic changes, often not accepted in their time. Given our poor success rates in resuscitation, it is evident that opportunities abound for improvement and innovation, hopefully within our lifetime.

AUTHOR: Austin Quinn, MD

FACULTY REVIEWER: Jamie Cohn, MD

Citations:

Oxilia, G., Fiorillo, F., Boschin, F. et. al. (2017). The dawn of dentistry in the late upper paleolithic: An early case of pathological intervention at riparo fredian. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 163(3), 446–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23216

de Smet PA, Hellmuth NM. A multidisciplinary approach to ritual enema scenes on ancient Maya pottery. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986 Jun;16(2-3):213-62. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90091-7. PMID: 3528674.

CPR through history. www.heart.org. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.heart.org/en/news/2018/05/01/cpr-through-history.

Dadmehr, M., Bahrami, M., & Eftekhar, B. et. al. (2018). Chest compression for syncope in medieval Persia. European Heart Journal, 39(29), 2700–2701. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy374.

Raju, T. N. K. (1999). History of neonatal resuscitation: Tales of heroism and desperation. Clinics in Perinatology, 26(3), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0095-5108(18)30041-1.

Watkins, Richard (1651). Newes from the Dead, or, A True and Exact Narration of the miraculous deliverance of Anne Greene, Who being Executed at Oxford Decemb. 14, 1650, afterwards revived; and by the care of certain physicians there, is now perfectly recovered. Together with the manner of her Suffering, and the particular means used for her Recovery. Written by a Scholler in Oxford for the Satisfaction of a friend, who desired to be informed concerning the truth of the businesse. Whereunto are added certain Poems, casually written upon that Subject. Oxford: Leonard Lichfield.

Morens, David M. (December 1999). "Death of a President". New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (24): 1845–1849. doi:10.1056/NEJM199912093412413.

Reid, S. (n.d.). A brief history of endotracheal intubation. Paediatric Emergencies. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.paediatricemergencies.com/intubationcourse/course-manual/history-of-intubation/.

Drew BA. Arthur Guedel and the Ascendance of Anesthesia: A Teacher, Tinkerer, and Transformer. J Anesth Hist. 2019 Jul;5(3):85-92. doi: 10.1016/j.janh.2018.08.002. Epub 2018 Aug 11. PMID: 31570202.

Driscol, Thomas E. (1975). The remarkable dr. Abildgaard and Countershock. Annals of Internal Medicine, 83(6), 878. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-83-6-878

Ball, C. M., Featherstone, P. J. (2019). Early history of defibrillation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 47(2), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057x19838914

J.A. Meyer, “Claude Beck and cardiac resuscitation”, Ann Thorac Surg. 45 (1988):103-5.

Okabe, R., Chen-Yoshikawa, T. F., Yoneyama, Y., et. al (2021). Mammalian enteral ventilation ameliorates respiratory failure. Med, 2(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.004

Lamba, Nayan; Holsgrove, Daniel; Broekman, Marike L. (2016). "The history of head transplantation: a review". Acta Neurochirurgica. 158 (12): 2239–2247. doi:10.1007/s00701-016-2984-0.

Photo Sources:

http://www.strangehistory.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Mayan-Enema.bmp

https://allthatsinteresting.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/two-smoke.jpg

https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/e7fb1690119ad229b77d1ffde882ff2475876830/3-Figure1-1.png

https://litfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/airway-the-dog-of-Arthur-Ernest-Guedel.jpeg