POCUS for Appendicitis

Case:

A previously healthy 8 year-old male presents to the ED with two days of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever. Pain was initially located in the periumbilical area, but has now migrated to the right lower quadrant. On exam, the patient has tenderness to palpation over the right lower quadrant and suprapubic areas. Lab work is notable for a leukocytosis.

Background:

We have all heard this story before. After all, the overall lifetime risk for appendicitis is 6.7 % for females and 8.6 % for males in the USA.[i] Before we start pushing the stretcher towards the operating room, we need some proof though. Despite how common it is, diagnosing appendicitis can be difficult. Symptoms are frequently non-specific and overlap with several other disease processes. However, it is a no-miss diagnosis as complications, including perforation, abscess formation, and peritonitis, can be life threatening. In the ED, our goal is to get patients with appendicitis treated before any complications arise, while trying to avoid sending a patient with a healthy appendix to the OR for removal.

Is this patient is going home or to the OR?

Before sending the patient to radiology, there is another imaging modality to consider, that being the bedside ultrasound. It is becoming increasingly popular and can be an extremely useful tool in the ER. There are many advantages to using ultrasound to make your diagnosis. For one, ultrasound has no ionizing radiation, making it an optimal choice in young or pregnant patients. Also, ultrasound is more cost-effective and has broader availability than CT or MRI. And remember, there are other structures in the abdomen that you can visualize with ultrasound too. In a patient with abdominal pain of unclear etiology, consider scanning the renal and biliary systems, and consider a pelvic US for females with right lower quadrant pain.

How good is ultrasound for diagnosing acute appendicitis?

In a literature review, there was extremely variable diagnostic accuracy of US with sensitivities ranging from 44 % to 100 % and specificities ranging from 47 % to 99 %.[ii] This gap is due to variation in operator skill, body habitus, bowel gas, and differences in anatomy. The 2011 Appropriateness Criteria for suspected appendicitis state that in pediatric patients the sensitivity and specificity of graded-compression US can approach that of CT, without the use of ionizing radiation.[iii] Don’t feel bad if you cannot find the appendix at first. In the literature, there is a large range of frequency cited for appendix visualization, and you will get better with experience!

How to find it:

Set yourself up with the patient supine, pain controlled, relaxed, and have a good view of the ultrasound screen. Start with a high frequency linear transducer. Place the probe in the transverse position in the right upper quadrant and apply deep, graded compression to displace bowel gas. You should see liver, and large bowel in this location. Large bowel can be identified as a non-peristalsing structure with haustra and the presence of stool, gas or fluid.[iv]

Figure 1: Normal colon. Photo source: http://bowel-ultrasound.org/images.html

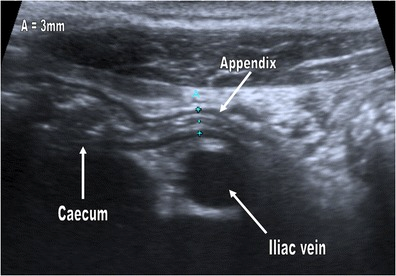

Trace the large bowel down to the cecum and identify the psoas muscle and the iliac vessels. The appendix can often be seen arising from the cecum, or draped above the iliac vessels just medial to the psoas muscle.

Figure 2: Appendix arising from the cecum. Photo source: http://ultrasoundconnection.com/word-of-the-day-appendicitis/

Figure 3: Inflamed appendix (arrow) draped over the psoas muscle. Photo source: http://posterng.netkey.at/esr/viewing/index.php? module=viewing_poster&task=viewsection&pi=126056&ti=418256&searchkey=

Figure 4: Photo source: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Samuel_Stafrace2/publication/256332872/figure/fig3/AS:202764446638091@1425354219309/A-normal-appendix-is-seen-draped-over-the-iliac-vessels-in-a-10-year-old-girl-This-is.png

Figure 5: Appendix draping over the iliac vessels. Iliac vessels shown using color Doppler

The Normal Appendix:

The appendix can be identified as a tubular, blind ending structure arising from the cecum. The normal appendix should be empty or filled with gas and fecal material. It should be compressible. Remember, a normal appendix is 8-10 cm in length, but some people can have a 20 cm long appendix! [v]

It is important to visualize the appendix arising from the cecum, as there are many other structures in the right lower quadrant that can mimic the appendix. Lymph nodes and small bowel are two such examples. Follow the appendix along its whole length. This is critical as appendicitis may only affect the tip. Your exam is not complete until you find that blind end.

Figure 6: Normal appendix tip. Photo source: http://www.ultrasoundpaedia.com/normal-appendix/

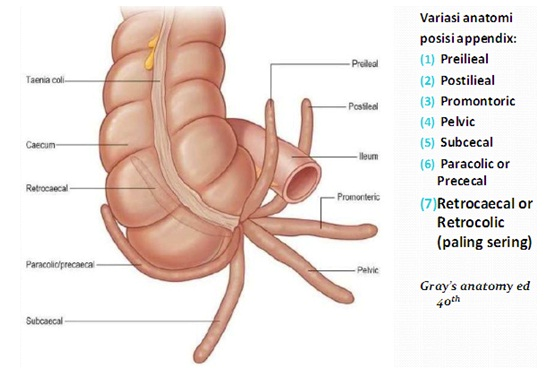

Remember, while the base of the appendix is usually found 2 cm below the ileocecal valve, the tip of the appendix can be located in variable locations.

Figure 7: Photo source: http://cephalicvein.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/appendix-location-dr-herry-setya-yudhautama-spb-finacs-mhkes-ics-digestive.jpg

If you clinically suspect appendicitis and the patient has a normal appendix, comprehensive imaging should follow. Repeating the exam after a few hours increases the sensitivity, so consider sending the patient home with instructions to return tomorrow if he or she is still symptomatic or admitting the patient for observation. Other options are an MRI when radiation protection is a priority (pediatric and pregnant patients) or a CT scan. [vi]

Tips and Tricks: [vii]

- A technique that can improve visualization of the appendix is the posterior manual compression technique. Use your left hand to press on the posterior aspect of the colon (and use your hand behind the patient to push anteriorly)

- Try scanning the patient with the right or left side down to move loops of bowel out of the way.

- If you are having trouble, try again after the patient has an empty bladder.

Abnormal Appendix:

If you suspect appendicitis, you can try having the patient put the probe on the most tender region on his or her abdomen. This will often give away the location of the appendix and is the fastest technique. Perform some graded compression in that region. If you see appendicitis and visualize the entire appendix, you are done! If not, start from the right upper quadrant using the method described above.

Findings supportive of the diagnosis of appendicitis include:

- A non-compressible appendix

- An appendix with an outer diameter measuring > 6 mm. Remember, that there are many normal appendixes that are >6 mm, and there are also abnormal appendixes <7 mm

- Wall thickness of 3 mm or greater

- Echogenic, inflammatory periappendiceal fat

- An appendicolith - an echogenic focus with a posterior acoustic shadow

- Localized tenderness with graded compression

- Secondary, supporting signs: Free fluid in the RLQ, periappendiceal fluid collection, increased echogenicity of the adjacent fat, or large mesenteric lymph nodes.

Of note, ultrasound has a lower sensitivity for a perforated appendix as the targetoid shape may not be maintained (you may not see the classic tubular structure).

Figure 8: Longitudinal and transverse, cross-sectional views of a distended, noncompressible appendix surrounded by hyperechoic/inflamed fat (arrows). Photo source: http://www.radiologyassistant.nl/data/bin/w440/a5097976c13458_inflamed-app.jpg

Figure 9: Ultrasound demonstrating a thickened appendix containing an echogenic, shadowing appendicolith. Photo source: https://images.radiopaedia.org/images/23961/de2254ff0c7343f84778b0451b1924_gallery.jpg

Fake Outs: [viii]

There are a few things that can be misinterpreted as appendicitis on US:

- Measuring small bowel instead of the appendix! Once you visualize what you think is the appendix, gently release pressure on the probe and make sure the appendix stays at approximately the same size on the ultrasound screen. If it expands significantly as pressure is released, you are likely getting fooled by small bowel.

- Mesenteric Adenitis. Patients with mesenteric adenitis may present with pyrexia and right lower quadrant pain. You will usually see multiple enlarged lymph nodes and a normal appendix in this diagnosis.

- Ovarian pathology in girls, such as torsion or a hemorrhagic cyst.

- Hydroureter from renal stones, which can appear tubular in shape and noncompressible.

- Meckel’s diverticulum. The leftover omphalomesenteric duct can appear as a non-compressible, blind ending structure. This can be confusing, but luckily it is not very common.

- Terminal ileitis from Crohn’s disease or infections (like Salmonella and Yersinia). On ultrasound, you would see bowel wall thickness <3 mm and you may see other features, such as perienteric fluid or fistulas.

Take Home Points:

- This is a difficult ultrasound to master. We see appendicitis often. Next time you have a patient with appendicitis, grab the probe and practice. Next time you have a thin patient without appendicitis, grab the probe and practice looking at a normal appendix. Practice makes perfect!

- Some studies are difficult, especially if the patient is obese. If it takes you more than 5 minutes to identify the appendix, consider thinking about alternative imaging.

- Remember, there are other structures in the abdomen that you can visualize with ultrasound that may mimic appendicitis. Consider scanning the renal and biliary systems. Consider a pelvic US for females with right lower quadrant pain.

- Remember, MRI is a great option in kids or pregnant patients!

- Visual learner? Dr. Adam Sivitz does an awesome how-to video. https://vimeo.com/152378669. Prefer podcasts? Check out www.ultrasoundpodcast.com.

Always try ultrasonography first! Remember, you can always get additional imaging studies to complement your amazing scans, if needed.

Resident Reviewer: Dr. TJ Ye

Faculty Reviewer: Dr. Erika Constantine

References:

[i] Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Nov;132(5):910-25.

[ii] Pinto F, Pinto A, Russo A, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adult patients: review of the literature. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-5-S1-S2.

[iii] Rosen MP, Ding A, Blake MA, Baker ME, Cash BD, Fidler JL, Grant TH, Greene FL, Jones B, Katz DS, Lalani T, Miller FH, Small WC, Spottswood S, Sudakoff GS, Tulchinsky M, Warshauer DM, Yee J, Coley BD. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® rightlower quadrant pain--suspected appendicitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011 Nov;8(11):749-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2011.07.010.

[iv] Quigley AJ, Stafrace S. Ultrasound assessment of acute appendicitis in paediatric patients: methodology and pictorial overview of findings seen.Insights into Imaging. 2013;4(6):741-751. doi:10.1007/s13244-013-0275-3.

[v] Park NH, Oh HE, Park HJ, Park JY. Ultrasonography of normal and abnormal appendix in children. World Journal of Radiology. 2011;3(4):85-91. doi:10.4329/wjr.v3.i4.85.

[vi] Mostbeck G, Adam EJ, Nielsen MB, et al. How to diagnose acute appendicitis: ultrasound first. Insights into Imaging. 2016;7(2):255-263. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0469-6.

[vii] Lee JH, Jeong YK, Park KB, Park JK, Jeong AK, Hwang JC. Operator-dependent techniques for graded compression sonography to detect the appendix and diagnoseacute appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Jan;184(1):91-7.

[viii] Quigley AJ, Stafrace S. Ultrasound assessment of acute appendicitis in paediatric patients: methodology and pictorial overview of findings seen.Insights into Imaging. 2013;4(6):741-751. doi:10.1007/s13244-013-0275-3.