Tuberculous Pleural Effusion

CASE

A 7 year-old girl presents to a hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi with worsening tactile fevers, shortness of breath, and productive cough over the past week. Her mother reports subjective weight loss, but denies night sweats, hemoptysis, or a significant respiratory history.

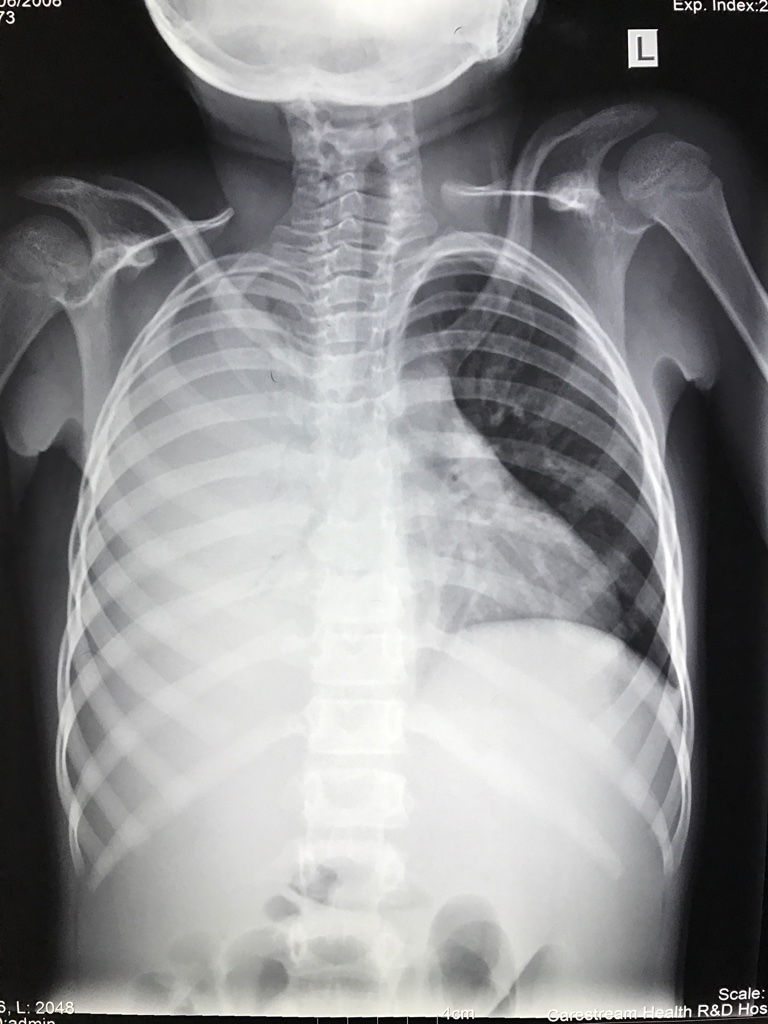

The patient’s vital signs were significant for a temperature of 100.6 F, pulse of 69, blood pressure of 107/72, tachypnea to 33, and hypoxia to 87% on room air. Her physical exam was notable for diminished breath sounds throughout the right side. An x-ray was performed revealing a large right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 1). A bedside ultrasound was then performed, showing a loculated pleural effusion (Figure 2). The patient underwent a therapeutic and diagnostic thoracentesis, returning straw colored fluid. In addition to standard pleural fluid studies, the patient’s fluid was also sent for Xpert MTB/RIF nucleic acid amplification test given the high prevalence of tuberculosis in the region, eventually returning a confirmatory diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Figure 1. Chest x-ray of a 7 year-old girl presenting with worsening shortness of breath, productive cough, and subjective fevers, found to have a large right-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 2. Still image of a point-of-care ultrasound performed on a 7 year-old girl with a large right-sided pleural effusion, showing a loculated pleural effusion.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Tuberculous pleural effusion

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The classic chest x-ray findings of primary pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) are parenchymal consolidation with or without hilar lymphadenopathy. Tuberculous pleural effusion (also known as tuberculous pleurisy) is the second most common form of extrapulmonary TB (after lymphatic involvement) (Figure 3), and is the most common cause of pleural effusions in TB endemic regions.[1] In children, tuberculous pleural effusion most often occur in the setting of primary TB,[2] whereas in adults they occur most frequently due to reactivation disease.[3] Patients typically present with an acute febrile illness with nonproductive cough and pleuritic chest pain, though dyspnea, night sweats, and weight loss can also occur. Most tuberculous pleural effusions are unilateral and, in contrast to our patient, small to moderate in size.[4] On chest x-ray, pleural disease is often appreciated.[5] Loculation of pleural effusions is not uncommon in tuberculous pleural effusion, and is thought to be due to direct pleural infection and the resulting intense intra-pleural inflammation and organization.[6]

Figure 3. Common sites of extrapulmonary TB.

DIAGNOSIS

Tuberculous pleural effusion should be suspected in patients with pleural effusion and TB risk factors including history of TB infection, TB exposure, or time spent in TB endemic regions. Unfortunately, definitive diagnosis of tuberculous pleural effusion can be challenging. Tuberculin skin test and interferon-gamma release assays do not distinguish between latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis disease, and thus cannot be used for definitive diagnosis. The gold standard of diagnosis remains demonstration of M. tuberculosis in pleural fluid or pleural biopsy specimen.[4] Presumptive diagnosis can reasonably be made in patients with a known history of pulmonary TB and a pleural effusion without any alternative cause.

In the undifferentiated patient, a workup for pulmonary TB should be initiated including sputum smear and culture for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Next, a diagnostic thoracentesis can be performed. Pleural fluid from tuberculous pleural effusion is typically an exudative, lymphocyte-predominant pleural effusion, and should be sent for smear and culture for AFB, though cultures are positive in less than 30% of HIV-uninfected patients,[4] and only approximately 50% of HIV-infected patients with CD4 counts less than 100 cells/mm3 (a higher sensitivity due to the greater bacterial burden).[7] Pleural fluid should also be sent for analysis, with typical findings shown in Table 1.

| Laboratory test | Typical finding |

|---|---|

| Color | Straw colored(14) |

| Protein concentration | >3.0 g/dL(15) |

| LDH | >500 international units/L(15) |

| pH | <7.4 |

| Glucose | 60-100 mg/dL(15) |

| ADA | >40 units/L |

| Cell count | 1,000-6,000 cells/mm^3.(16) Early neutrophil predominance. After the first few days, lymphocytes predominate.(15) |

A presumptive diagnosis can be made if there is a lymphocytic-to-neutrophil ratio >0.75 and ADA >40 units/L.[8-10] While nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests for M. tuberculosis that are FDA-approved for use with sputum have not yet been approved for pleural fluid in the United States, some laboratories use NAA testing of pleural fluid as a validated, "off-label" application. If the patient still remains undifferentiated after this testing and there is concern for the medically complex patient or suspected drug resistance, a pleural biopsy can be pursued by thoracoscopy or closed percutaneous needle biopsy with resulting tissue sample sent for AFB smear and culture as well as histopathology for evaluation of granulomas. Additionally, all patients with suspected tuberculous pleural effusions should be tested for HIV infection.

TREATMENT

The mainstay of treatment of tuberculous pleural effusion is antituberculosis therapy, the same as active pulmonary tuberculosis. A typical drug regimen consists of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 8 weeks, followed by isoniazid and rifampin for an additional 18 weeks. Empiric antituberculous therapy is warranted if a presumptive diagnosis is made as described above, and patients typically defervesce within two weeks and pleural fluid is resorbed within six weeks. However, some patients take up to two months to defervesce with fluid resorption taking up to four months. In areas with high rates of antituberculous drug resistance, organism isolation is more critical as it can guide drug selection. Currently, corticosteroids are not recommended as an adjuvant therapy as there is insufficient evidence for benefit.[11] Therapeutic thoracentesis can be considered in patients with larger pleural effusions or significant dyspnea, as it has been shown to more quickly resolve dyspnea, though there is no effect on long-term outcomes.[12,13]

DISPOSITION AND CASE CONCLUSION

Empiric antituberculosis therapy was initiated after thoracentesis, with resulting clinical improvement. The patient was soon thereafter discharged to complete the remainder of her antituberculosis therapy through a directly observed therapy (DOT) program and was doing well at her follow up visit.

TEACHING POINTS

Tuberculosis is the most common cause of pleural effusions in endemic regions.

The gold standard of diagnosis is demonstration of M. tuberculosis in pleural fluid or pleural biopsy specimen.

A presumptive diagnosis can be made if pleural fluid shows a lymphocytic-to-neutrophil ratio >0.75 and ADA >40 units/L.

Treatment of tuberculous pleural effusions is the same as for pulmonary tuberculosis.

Faculty Reviewer: Dr. Lauren Allister

REFERENCES

Zhai, K, Lu, Y, Shi, HZ. Tuberculous pleural effusion. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E486-94.

Merino, JM, Carpintero, I, Alvarez, T, Rodrigo, J, Sanchez, J, Coello, JM. Tuberculous pleural effusion in children. Chest 1999;115:26-30.

Torgersen, J, Dorman, SE, Baruch, N, Hooper, N, Cronin, W. Molecular epidemiology of pleural and other extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a Maryland state review. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1375-82.

Gopi, A, Madhavan, SM, Sharma, SK, Sahn, SA. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous pleural effusion in 2006. Chest 2007;131:880-9.

Seibert, AF, Haynes, J, Jr., Middleton, R, Bass, JB, Jr. Tuberculous pleural effusion. Twenty-year experience. Chest 1991;99:883-6.

Ko, Y, Kim, C, Chang, B, Lee, SY, Park, SY, Mo, EK, et al. Loculated Tuberculous Pleural Effusion: Easily Identifiable and Clinically Useful Predictor of Positive Mycobacterial Culture from Pleural Fluid. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2017;80:35-44.

Gil, V, Cordero, PJ, Greses, JV, Soler, JJ. Pleural tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients. Chest 1995;107:1775-6.

Light, RW. Update on tuberculous pleural effusion. Respirology 2010;15:451-8.

Sahn, SA, Huggins, JT, San Jose, ME, Alvarez-Dobano, JM, Valdes, L. Can tuberculous pleural effusions be diagnosed by pleural fluid analysis alone? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:787-93.

Jimenez Castro, D, Diaz Nuevo, G, Perez-Rodriguez, E, Light, RW. Diagnostic value of adenosine deaminase in nontuberculous lymphocytic pleural effusions. Eur Respir J 2003;21:220-4.

Ryan, H, Yoo, J, Darsini, P. Corticosteroids for tuberculous pleurisy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD001876.

Bhuniya, S, Arunabha, DC, Choudhury, S, Saha, I, Roy, TS, Saha, M. Role of therapeutic thoracentesis in tuberculous pleural effusion. Ann Thorac Med 2012;7:215-9.

Lai, YF, Chao, TY, Wang, YH, Lin, AS. Pigtail drainage in the treatment of tuberculous pleural effusions: a randomised study. Thorax 2003;58:149-51.

Levine, H, Metzger, W, Lacera, D, Kay, L. Diagnosis of tuberculous pleurisy by culture of pleural biopsy specimen. Arch Intern Med 1970;126:269-71.

Epstein, DM, Kline, LR, Albelda, SM, Miller, WT. Tuberculous pleural effusions. Chest 1987;91:106-9.

Valdes, L, Alvarez, D, San Jose, E, Penela, P, Valle, JM, Garcia-Pazos, JM, et al. Tuberculous pleurisy: a study of 254 patients. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:2017-21.