Non-Accidental Trauma

Case

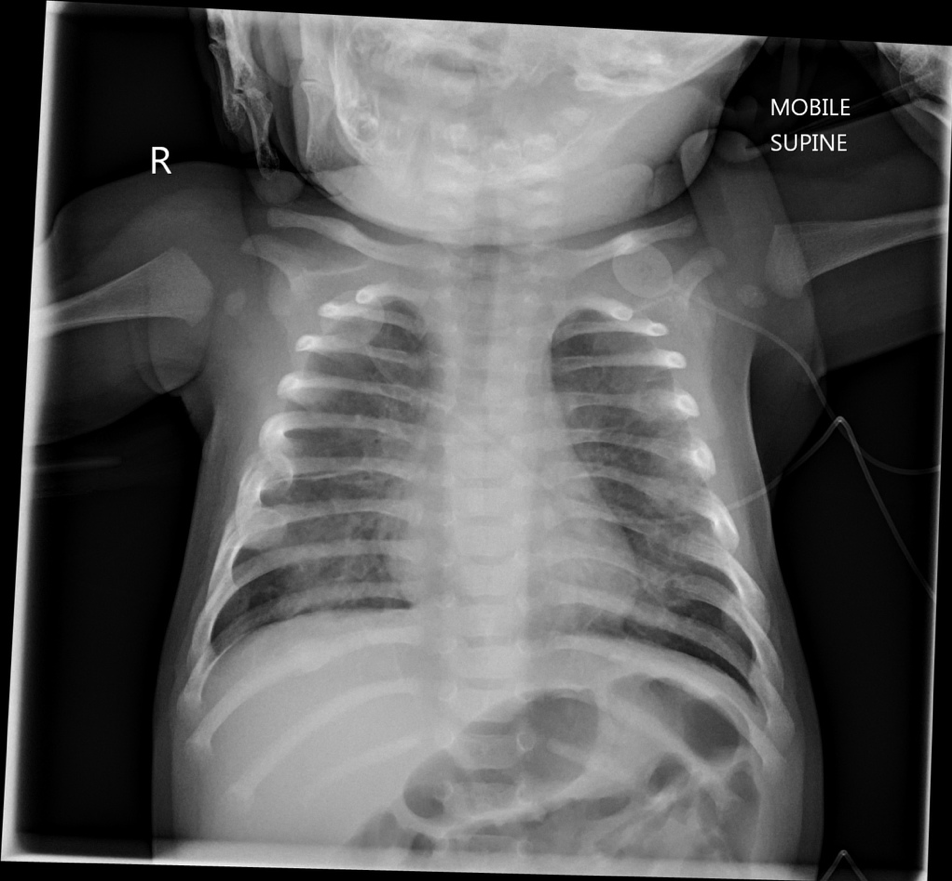

A hypothetical 7 month-old infant presents to the emergency department for mild respiratory distress. There is no recent illness or symptoms to explain the infant’s tachypnea and mild hypoxia. There is no visible bruising on exam. The parent states that the infant is starting to pull to stand but does not yet cruise. They have had several falls onto their tile kitchen floor. The CXR (below) is read by the radiologist left posterior rib fractures in ribs 4-8.

Case courtesy of Dr. George Harisis, Radiopaedia.org. From the case Non-Accidental Injury

Highly Specific Fracture Patterns for Non-Accidental Trauma

A helpful adage: “Those that don’t cruise rarely bruise.” Approximately 80% of NAT occur in children less than 18 months old. A study evaluating bruising in normal infants demonstrated that only 0.01% (6 of 465) of pre-cruisers had ecchymoses. Soft tissue findings, like bruises, may tip you off to underlying or fractures either underlying or elsewhere. Pierce et al. (2010) highlighted the value of the TEN 4 FACES mnemonic to highlight concerning bruises that should prompt a workup for NAT: bruises to the Torso, Ears, and Neck in children < 4, any bruising on immobile children < 4 months, or bruising to the Frenulum, Angle of the mandible, Cheek, Eyelid, or Sclera.

Fractures are the second most common finding in pediatric non-accidental trauma after bruising or other soft-tissue injuries. Although there are often similar fracture patterns seen in both accidental and non-accidental trauma, the fractures described below are the most highly specific for non-accidental trauma and should heighten your suspicion for intentional physical abuse:

Metaphyseal Fracture (aka “Corner” or “Bucket Handle” fractures)

A metaphyseal fracture is made up of microfractures perpendicular to the long axis of the bone, most commonly the distal ends of the tibia, femur, humerus. These microfractures are caused by the shearing forces of ligaments when a child who cannot control their limbs is shaken forcefully while held around their torso. It is highly specific fracture and is almost universally considered pathognomonic for non-accidental trauma.

Case courtesy of Dr. Basab Bhattacharya, Radiopaedia.org. From the case Non-Accidental Injuries

Case courtesy of Dr. JR Dwek. From the The Radiographic Approach to Child Abuse.

Posterior Rib Fractures

Posterior rib fractures occur when enough anteroposterior chest compression is generated to cause movement of the posterior rib that acts as a lever over the transverse spinal process. This, like with metaphyseal fractures, can be caused by holding and shaking an infant with two hands around the ribcage. Other mechanisms include “marked forward decceleration into a solid object” in MVCs or in other non-accidental trauma. Biomechanically, the amount of force needed to cause leverage against the transverse process cannot be replicated when the patient is lying with their back against a flat surface, as is the case in CPR. A small post-mortem study of infants that had received even two-handed CPR supports this: they found anterolateral fractures but no occurrences of posterior rib fractures. In studies by Kleinman et al. (1997) and by Barsness et al. (2003) Posteromedial rib fractures have a very high positive predictive value (95%) for NAT and have the highest specificity for NAT.

Case courtesy of Dr. Paula Brill, Radiopaedia.org. From the case Non-Accidental Trauma.

The Three S’s: Spinous Process, Scapular, and Sternal Fractures

Though seen less often, spinous process, scapula, and sternum fractures round out the top most specific fractures for non-accidental trauma. Sternum and scapular fractures occur in the setting of a direct blow of unusual amounts force and are unexplained in the normal handling of most infants. As with other fractures, it is important to determine if the provided history matches the mechanism.

Other Specific Fracture Findings

Clavicular fractures (after the period explained by birth trauma)

Epiphyseal separations

Vertebral body fractures/separations

Digital fractures

Complex skull fractures

Next Steps

Mandatory reporting to Child Protective Services

Per the American Academy of Pediatrics, all patients undergoing workup for non-accidental trauma should be admitted to the hospital.

Complete a skeletal survey, which involves approximately 21 x-rays focusing on each individual limb or body part.

Order a CT brain to evaluate both the skull and underlying brain. Reconstructions of specific CTs may allow rotation of images and better identification of fractures.

What Are We Missing?

In the most recent data published by the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, there were 1,585 fatalities due to child abuse and neglect in 2015. Approximately 44% percent of those suffered death due to physical abuse and almost 75% were children <3 years old.

A small study comparing known instances of child abuse fatalities with local medical records found that 30% of children who subsequently died from non-accidental trauma had interactions with health care for reasons other than well-child checks. Nearly 20% of those visits occurred within one month of their death. Albeit brief, emergency department visits may be the only interaction these children have with the health care system represent a critical opportunity for intervention.

Faculty Reviewer: Dr. Adam Aluisio

References

Baldwin K, Pandya NK, Wolfgruber BA, et al. Femur Fractures in Pediatric Population: Abuse or Accidental Trauma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 Mar; 469(3):798-804.

Barsness KA, Cha ES, Bensard DD, Calkins CM, Partrick DA, et al. The positive predictive value of rib fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma. 2003;54:1107–1110.

Bechtel K. Physical Abuse of Children: Epidemiology of Child Abuse in the United States. Emergency Medicine Reports. 2003 Mar.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2017). Child abuse and neglect fatalities 2015: Statistics and interventions. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

Christian CW. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The Evaluation of Suspected Child Physical Abuse. Pediatrics. 2015; 135(5):1337-1354.

Dwek JR. The Radiographic Approach to Child Abuse. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2011;469(3):776-789.

King WK, Kiesel EL, Simon HK. Child Abuse Fatalities: Are We Missing Opportunities for Intervention? Pediatric Emerg Care. 2006;22(4):211-214.

Kleinman PK, Perez-Rossello JM, Newton AW, et al. Prevalence of the classic metaphyseal lesion in infants at low versus high risk for abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Oct;197(4):1005-8.

Kleinman PK, Schlesinger AE. Mechanical factors associated with posterior rib fractures: laboratory and case studies. Pediatr Radiol. 1997(27): 87-91.

Leaman LA, Hennrikus WL, Bresnahan JJ. Identifying non-accidental fractures in children aged <2 years . Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics. 2016;10(4):335-341.

Matshes EW, Lew EO. Two-Handed Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Can Cause Rib Fractures In Infants. Amer Journal of Forensic Med and Pathology. 2010 Dec; 31(4): 303-307.

Paddock M, Sprigg A, Offiah AC. Imaging and reporting considerations for suspected physical abuse (non-accidental injury) in infants and young children. Part 1: initial considerations and appendicular skeleton. Clinical Radiology. 2017 Mar;72(3):179-188

Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Aldridge S, O'Flynn J, Lorenza DJ. Bruising Characteristics Discriminating Physical Child Abuse From Accidental Trauma. Pediatrics. 2019;125(1):67-74.

Sugar NF, Taylor JA, Feldman KW, and the Puget Sound Pediatric Research Network. Bruises in Infants and Toddlers Those Who Don't Cruise Rarely Bruise. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):399–403.