Acromioclavicular Joint Injury

Case

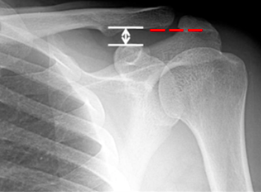

A 19 year-old male presents to the emergency department with a complaint of right shoulder pain. He was tackled from behind in a rugby game three days prior to presentation and has been experiencing pain over the anterior aspect of his right shoulder since that time. Physical exam is notable for tenderness over the right acromioclavicular (AC) joint and pain with both active and passive range of motion of the right shoulder. X-rays (Figure 1) show “no obvious fracture or subluxation.” However, based on your exam and clinical suspicion, closer inspection reveals abnormal alignment between the clavicle and the acromion consistent with AC joint injury.

Figure 1

The Acromioclavicular Joint

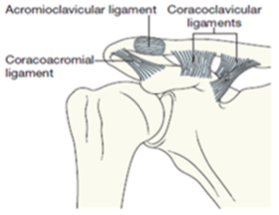

The acromioclavicular joint is formed by the AC ligament and the coracoclavicular (CC) ligament (Figure 2). The AC ligament provides horizontal stability to the joint while the CC ligaments provide vertical stability. (1)

In normal configuration, the inferior cortices of the clavicle and acromion are in alignment (Figure 3). Additionally, the coracoclavicular distance is normally less than 13 mm or there is a less than 5 mm difference between the left and right coracoclavicular distances. (1; 3) Figure 4 depicts normal alignment of the inferior cortices of the acromion in red and highlights the coracoclavicular distance in white.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Mechanism of Injury, Physical Examination, and Diagnosis

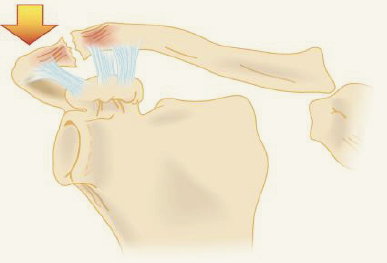

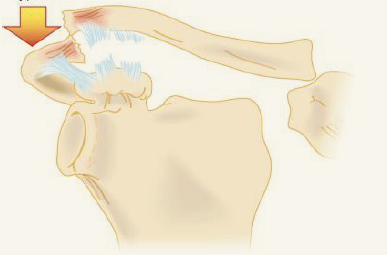

Acromioclavicular joint subluxation and dislocation account for approximately 10% of all traumatic shoulder injuries. (1; 3) AC joint injury results from either direct or indirect injury to the shoulder. Direct injury to the joint occurs with a direct blow to the shoulder or, more commonly, when an individual falls with their arm in an adducted position. Indirect injury to the AC joint typically occurs as a result of a fall on an outstretched hand. (1; 4) On exam, patients will have pain over the acromioclavicular joint and pain with range of motion of the shoulder. (3) Patients may hold their arm in an adducted position and there may be a visible or palpable step-off deformity over the AC joint. Additionally, the ipsilateral clavicle may appear to be high-riding or the ipsilateral shoulder may appear displaced inferiorly (Figure 5). (1; 3) In less obvious cases, provocative maneuvers (such as the cross-body adduction test and AC shear test) may be used to localize discomfort to the AC joint. (2)

If acromioclavicular joint injury is suspected, three-view radiographs of the shoulder (anteroposterior view, scapular-Y view, axillary view) and a Zanca view (a specialized anteroposterior radiograph which removes the scapula from behind the joint) allow for identification of vertical displacement of the clavicle and for anteroposterior displacement of the clavicle. (2) AP comparison views of both AC joints can also be helpful in diagnosis of AC joint injury.

Figure 5

Acromioclavicular Joint Injury: Rockwood Classification

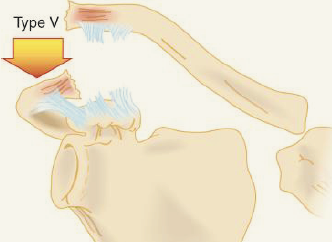

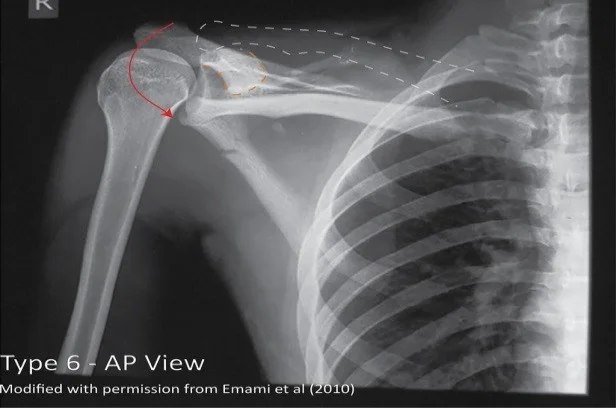

Acromioclavicular joint injuries are characterized by the degree of damage to the AC ligament and the CC ligaments. (3). These injuries are further classified using the Rockwood System (Figure 6).

| Type I | Figure 6 AC Ligament Sprain |  |

|

| Type II | AC Ligament Rupture |

|  |

| Type III | AC Ligament Rupture |

|  |

| Type IV | AC Ligament Rupture |

|  |

| Type V | AC Ligament Rupture |

|  |

| Type VI | AC Ligament Rupture |

|  |

Management

Non-Operative Management

Type I and Type II AC joint injuries are managed non-operatively. Patients should be immobilized in a sling for 7-14 days and should then proceed with progressive range of motion exercises. Return to full activity is indicated when patients are pain-free. (1; 3)

Type III AC joint injuries are often managed non-operatively with immobilization in a sling and range of motion/strengthening exercises. These individuals should be referred for outpatient orthopedic follow-up. (1)

Operative Management

Urgent orthopedic referral is indicated in patients with neurovascular compromise, skin tenting, and significant deformity. Additionally, Type IV-VI AC injuries are typically managed surgically and, as such, require urgent orthopedic consultation.

Case Outcome

The patient’s radiograph and clinical exam was most consistent with a Type III acromioclavicular joint injury. He was immobilized in a sling, provided with prescriptions for ibuprofen and acetaminophen, and instructed to follow up with orthopedics for further evaluation on an outpatient basis.

Faculty Reviewer: Dr. Jeffrey Feden

References

Egol, K. A., Koval, K. J., & Zuckerman, J. D. (2010). Handbook of fractures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Koehler, Scott M. (2018). Acromioclavicular joint disorders. UpToDate. < https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acromioclavicular-joint-disorders?search=acromioclavicular%20joint§ionRank=2&usage_type=default&anchor=H9685354&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~35&display_rank=1#H9685354>.

Marx, J., Walls, R., & Hockberger, R. (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine-Concepts and Clinical Practice E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Tintinalli, J. (2015). Tintinallis emergency medicine A comprehensive study guide. McGraw-Hill Education.

Images

Figure 1: Case courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/30774">rID: 30774</a>

Figure 2: Egol, K. A., Koval, K. J., & Zuckerman, J. D. (2010). Handbook of fractures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Figure 3: Richardson, Michael L. (1998). Radiographic anatomy of the skeleton: Shoulder—Internal rotation view. Obtained from <http://uwmsk.org/RadAnat/IntRotLabelled.html>.

Figure 4: Kang, K. S., Lee, H. J., Lee, J. S., Kim, J. Y., & Park, Y. B. (2009). Long term follow up results of the operative treatment of the acromioclavicular joint dislocation with a Wolter plate. Journal of the Korean Fracture Society, 22(4), 259-263.

Figure 5: Greene, Tim (ND). CoreEM: Acromioclavicular joint injury. Obtained from <https://coreem.net/core/ac-joint-injuries/>.

Figure 6:

Type I: Case courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/28623">rID: 28623</a>

Type II: Case courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/60140">rID: 60140</a>

Type III: Case courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/30949">rID: 30949</a>

Type IV: Case courtesy of Dr Craig Hacking, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/64411">rID: 64411</a>

Type V: Case courtesy of Dr Bruno Di Muzio, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/44768">rID: 44768</a>

Type VI: Case courtesy of Dr Jeffrey Hocking, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/48600">rID: 48600</a>