The Febrile Seizure

BACKGROUND

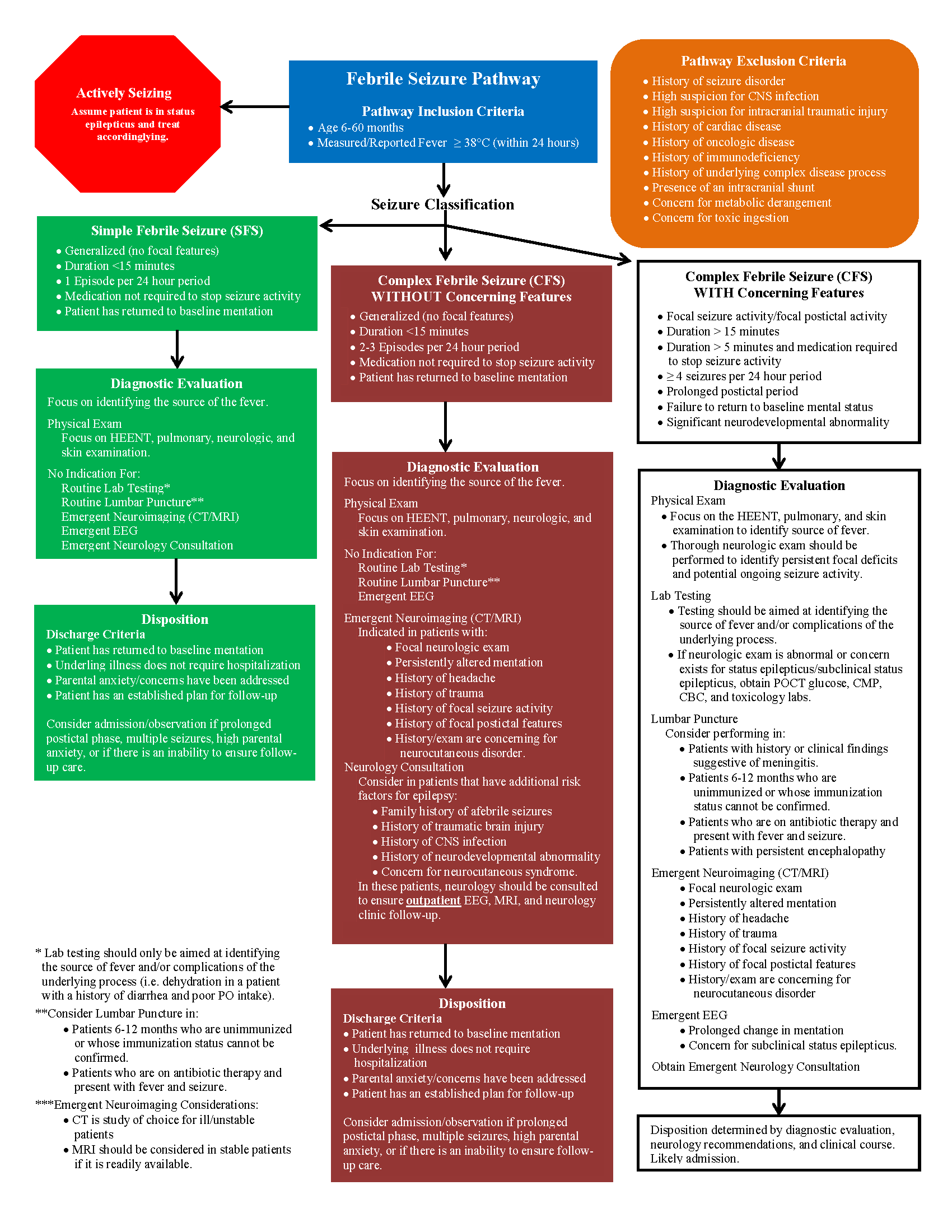

2-4% of children under the age of 5 years will experience a febrile seizure and, of those affected, up to 30% of will have recurrent episodes. [1] Despite how frequently emergency physicians encounter children who have had a febrile seizure, there tends to be great variation in the diagnostic evaluation of these patients. The algorithm below was created to provide a more simplified approach to the patient presenting with a febrile seizure. The algorithm draws from the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Febrile Seizure as well as the clinical pathways published by Seattle Children’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Dell Children’s Medical Center, and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals.

Definition of febrile seizure

A convulsive episode occurring in a child aged 6 months to 5 years with a body temperature of >38°C. [1,4] Patients with febrile seizures cannot have a prior history of afebrile seizures and the episode must occur in the absence of a central nervous system infection or metabolic abnormality known to induce seizure activity. [1,4]

Classification

Simple febrile seizure. Generalized febrile convulsions which persist for less than 15 minutes, do not recur within a 24 hour period, do not require medication for termination, and do not have a prolonged postictal period. [1,4,6,8,9]

Complex febrile seizure. Either generalized or focal in nature, persist between 15 and 30 minutes in duration, and/or a febrile seizure which recurs within a 24 hour period. [1,4,7,9] The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia further classifies complex febrile seizures into those with “concerning features” and those “without concerning features.” [6] As this distinction carries important diagnostic considerations, it has been adopted into the algorithm above.

Complex febrile seizures without “concerning features” refer to febrile seizures which are generalized, persist for less than 15 minutes, have 2-3 occurrences in a 24 hour period, do not require medication to terminate, and are not associated with a prolonged postictal phase. [6]

Complex febrile seizures with “concerning features” refer to febrile seizures with associated focal ictal/postictal activity, a duration longer than 15 minutes, a duration longer than 5 minutes requiring medication for termination of seizure activity, for or more seizures in a 24 hour period, and if there is a prolonged postictal period/failure to return to baseline mental status. [6] Additionally, the presence of an underlying significant developmental abnormality is felt to represent a “concerning feature.” [6]

Febrile status epilepticus. Febrile seizure which has persisted for greater than 30 minutes duration or a series of intermittent febrile seizures occurring without neurologic recovery for a period of 30 minutes or longer. [1,4] As shown in the algorithm above, if a patient presents actively seizing, they should be assumed to be in status epilepticus and treated accordingly.

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Lab testing

In children presenting with a simple febrile seizure who have a reassuring neurologic exam, diagnostic evaluation should focus on identifying the underlying cause of the patient’s febrile illness and complications of the associated illness. [1,3,4,5] This recommendation is based upon the finding that children with simple febrile seizures have the same incidence of serious bacterial infection as age-matched controls who present with a fever and no history of seizure activity. [2] In complex febrile seizures with concerning features such as focal seizure activity, focal postictal findings, and prolonged seizure activity, there is a higher likelihood of meningitis, significant metabolic anomaly, or associated central nervous system structural abnormality. [2] As such, these patients tend to require a broader diagnostic evaluation.

Lumbar puncture

As noted by the AAP, there is no indication for routine lumbar puncture in most patients presenting with a simple febrile seizure. [4,5] The AAP does recommend considering a lumbar puncture in simple febrile seizures in patients 6-12 months of age who are unimmunized, in children 6-12 months whose immunization status cannot be confirmed, and in children presenting with a simple febrile seizure after being treated with antibiotics. [5] The AAP has no guidelines for the role of the lumbar puncture in the diagnostic evaluation of patients presenting with complex febrile seizures. As discussed by Whelan et. al, current literature suggests that the overall risk of bacterial meningitis in this population is low. [4]. Accordingly, the decision to pursue a lumbar puncture should be made on a case-by-case basis with strong consideration in patients with a complex febrile seizure and history/exam concerning for meningitis/encephalitis, patients who are unimmunized/under-immunized, patients pretreated with antibiotic therapy, patients who are less than 12 months of age (as the clinical findings of meningitis are subtle), and in patients with persistent encephalopathy. [4,6]

Neuroimaging

The AAP recommends against the use of routine neuroimaging (CT/MRI) in children presenting with a simple febrile seizure. [4,5] There are no formal guidelines regarding the use of neuroimaging in complex febrile seizures. [4] However, there is a role for emergent neuroimaging in patients with a history or clinical exam suggestive of head trauma, a history of headache, focal seizure/postictal activity, and if history and exam are concerning for an underlying neurocutaneous disorder. [4] In patients who present with a complex febrile seizure without “concerning features,” outpatient neuroimaging is recommended in patients who have additional risk factors for epilepsy-family history of afebrile seizures, history of traumatic brain injury, history of CNS infection, history of neurodevelopmental delay, and history/exam concerning for neurocutaneous syndrome. [4,8]

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

In children with a simple febrile seizure, the AAP recommends against performing routine EEG. [4,5] Emergent EEG should be obtained when there is a concern for subclinical seizure activity or non-convulsive status epilepticus. [4]. Neurology referral and routine EEG should be considered in children presenting with complex febrile seizures with focal seizure activity, focal postictal features, and/or additional risk factors for epilepsy. [4]

Neurology Consultation

Emergent neurology consultation is indicated in patients who present in febrile status epilepticus, in patients who present after a complex febrile seizure with a persistently abnormal neurologic exam. [4,7] Emergent neurology consultation should also be considered in patients who have had a history of multiple complex febrile seizures and in patients who present after a complex febrile seizure who have additional risk factors for epilepsy. [4]

Authors:

Alexander Dayton, MD is a second year resident in emergency medicine at Brown University

Meghan Beucher, MD is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Brown University

REFERENCES

Millichap, John. 2020. Clinical Features and Evaluation of Febrile Seizures. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-evaluation-of-febrile-seizures?search=febrile%20seizure&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H91723936

Helman, Anton. 2015. Emergency Management of Pediatric Seizures. Emergency Medicine Cases. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/emergency-management-of-pediatric-seizures/

Millichap, John. 2020. Treatment and Prognosis of Febrile Seizures. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prognosis-of-febrile seizures?search=febrile%20seizure&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~138&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

Whelan, H., Harmelink, M., Chou, E., Sallowm, D., Khan, N., Patil, R., ... & Bajic, I. (2017). Complex febrile seizures-A systematic review. Disease-a-month: DM, 63(1), 5.

Seizures, F. (2011). Guideline for the neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure subcommittee on febrile seizures. Pediatrics, 127(2), 389-394.

Hart, J.; Blackstone, M.; Dorland, K.; Bearden, D.; Sergonis, M.; Scheid, V.; Kaur, T.; Haas, S.; Adang, L. (2018). Children's Hospital of Philadelphia ED and Inpatient Pathway for the Evaluation/Treatment of the Child with Febrile Seizures without Neurologic Disease. Available from https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/febrile-seizures-without-known-seizure-disorder-emergency-and-inpatient-clinical-pathway

Dell Children's Medical Center; Iyer, M.; Clark, D.; Ngo, T.; Martino, O.; Toth, B.; Boswell, P. (2017). Dell Children's Medical Center Evidence-Based Outcomes Center Febrile Seizure and New Onset Afebrile Seizure. Available from: https://www.dellchildrens.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2019/08/DCMCFebrileNewOnsetAfebrileSeizureManagementGuideline.pdf

Seattle Children's Hospital; Morgan, L.; Ackley, SH; Fenstermacher, S.; Hrachovec, J.; Migita, D. (2019). Febrile Seizure Pathway. Available from: https://www.seattlechildrens.org/pfd/febrile-seizures-pathway.pdf.

Bin, Steven, (2017). Febrile Seizures-Assessment and Acute Management. UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. Available from https://www.ucsfbenioffchildrens.org/pdf/pem_guidelines/febrile_seizures.pdf