Banging Bungies: Viewing Traumatic Eye Injuries Through a New Lens

CASE

A 53-year-old male with a PMH of GERD presents to the emergency department with eye pain, photophobia, and vision loss after getting popped in the eye by a broken bungee cord. He believes the tip of the cord came around “like a whip” and struck him directly on the eye.

On exam he is sitting in a darkened room with an eye patch covering his left eye. He appears uncomfortable. He has bilateral scleral injection and an abrasion over the left zygomatic bone.

OD: mild scleral injection, pupil 5 mm and reactive, extraocular movement intact but pain limited by contralateral eye. 20/40

OS: Scleral injection, anterior chamber is hazy without fluid level, pupil is irregular and nonreactive, and the patient reports shadows to hand waving in front of face. Fluorescein dye shows minor 1-2 mm filling defect lateral to the pupil at 3 o’clock. Initial tonometry pen pressure is 37 mmHg.

Bedside Ultrasound is performed as below:

Figure 1: Ocular POCUS showing circular ring shaped hyperechoic area in the posterior chamber.

DIAGNOSIS

Traumatic lens dislocation

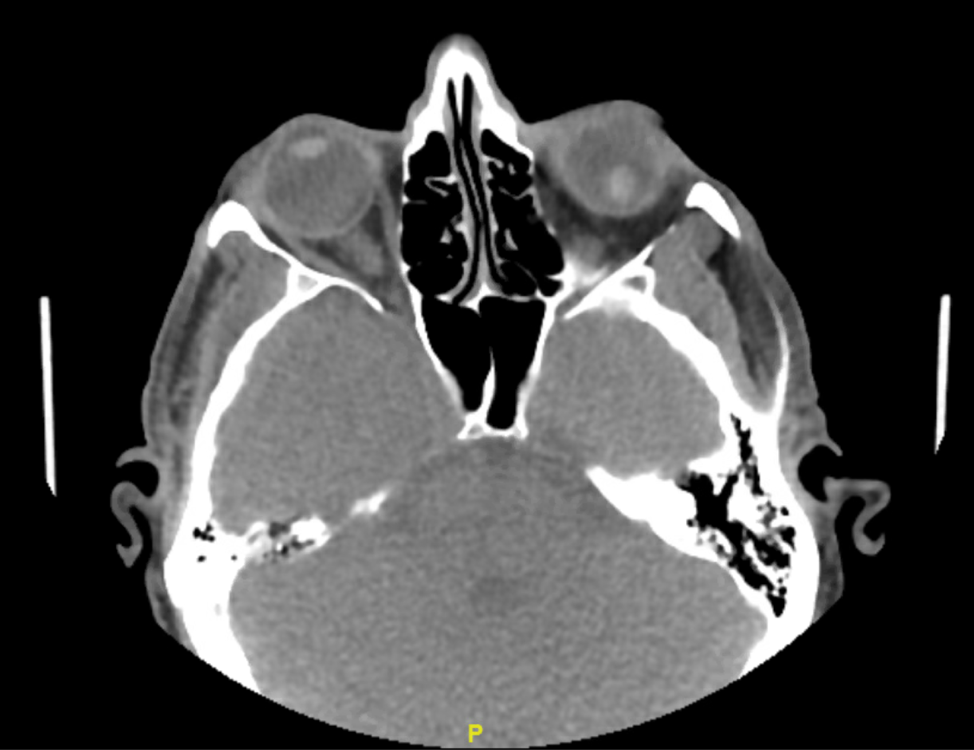

Figure 2: CT face with confirmation of lens detachment

DISCUSSION

Eye trauma is reportedly present in 1.5% of emergency department visits, but lens dislocation, or ectopia lentis, makes up a low proportion of those visits overall. [1] Although connective tissue disorders such as Marfans syndrome can lead to spontaneous dislocation, far more commonly this injury follows trauma. [2] When the trauma is mild, however, consider further outpatient evaluation for underlying genetic or acquired connective tissue disease.

Lens dislocation is a vision-threatening injury and if missed could lead to permanent vision loss due to elevated intraocular pressures (IOP) from posttraumatic angle recession. Therefore prompt diagnosis, particularly in intubated or comatose patients, is warranted and can be accomplished by bedside Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS).

Figure 3: Ocular POCUS with normal lens location

Here we propose the following stepwise approach to traumatic eye complaints: physical exam, visual acuity, tonometry pen, fluorescein, POCUS. A very astute ED resident might see “eye complaint” on the board and bring an ultrasound into the room during the initial interview and perform it after the physical exam and before tonopen or fluorescein staining.

In the case of Ectopia lentis due to trauma, the history will reveal direct contact with the eye, or orbit usually in an anterior-posterior direction, associated with vision loss or distortion. Patients may also report monocular diplopia as well as severe pain, photophobia, and consensual photophobia.

The physical exam will note severely decreased visual acuity. The sclera may be injected or chemotic (the latter should make you very concerned for serious injury). The anterior chamber may show a hyphema. If the anterior chamber is quiet, one might see an irregularly-shaped, minimally reactive pupil. Even with an ophthalmoscope, you will not be able to visualize the retina because the lens no longer focuses the light on the back of the eye leading to loss of the red reflex.

When compared with the gold standard of CT scan, POCUS is a sensitive (96.8%) and very specific (99.4%) modality for diagnosis of traumatic lens dislocation presenting to the emergency department. [1] Here is a good summary of how to perform an ocular ultrasound. Remember, copious amounts of ultrasound gel on top of a tegaderm is advised. Here are some additional resources on performing ocular ultrasound in the ED.

While it may seem obvious: DO NOT PUT PRESSURE ON AN OPEN GLOBE. If the patient has signs or symptoms of an open globe do not use US or tonometry.

With traumatic lens dislocation you will see an empty space where the lens normally sits. If you are fortunate and the posterior chamber is free of debris (such as from retinal detachment or vitreous hemorrhage) you may be able to see the lens floating inside the posterior chamber of the eye. As a reminder, fan all the way through the eye in two planes with the ultrasound probe, because as Dr. Tubbs says “one view is no view,” and it is helpful to know if any other pathology is present.

Many providers work in ED settings without 24-hour ophthalmology coverage, and deciding who should be transferred to tertiary care and who can be discharged home is paramount. It should be noted then that becoming comfortable with ultrasound, specifically ocular ultrasound, can be a light when things seem dark.

TREATMENT

Surgery is the mainstay of therapy, and delayed correction may be appropriate if the patient is otherwise uninjured and reliable for follow up. Emergent surgery is indicated if other sight-threatening pathology is present such as open globe, retinal detachment or retrobulbar hematoma.

CASE RESOLUTION

Because the patient had increasing intraocular pressures, he was started on topical IOP reducers, pain management, and finally IV Diamox (500mg). Over the course of his ED stay, he was able to transition to oral Diamox with continued improvement in his eye pain. Ultimately he discharged home with outpatient ophthalmology follow up for surgical correction 5 days later.

TAKE-AWAYS

Perform the same evaluation on every eye complaint including ultrasound. Fan through the entire globe in both planes, for both eyes.

Ultrasound is both very sensitive and very specific for lens dislocations.

Look for other traumatic eye injuries, especially in patients who are comatose or with altered mental status.

Lens dislocation requires at minimum urgent ophthalmology follow-up and surgery.

If trauma is minor consider other genetic causes.

AUTHOR: Russell Prichard, MD is a third-year emergency medicine resident at Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital.

FACULTY REVIEWER: Kristin Dwyer, MD, MPH is Assistant Professor at Brown University, Director of Emergency Ultrasound Division, and Director of Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship.

REFERENCES

Ojaghihaghighi S, Lombardi KM, Davis S, Vahdati SS, Sorkhabi R, Pourmand A. Diagnosis of Traumatic Eye Injuries With Point-of-Care Ocular Ultrasonography in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;74(3):365-371. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.02.001. Epub 2019 Mar 21. PMID: 30905470.

Eken C, Yuruktumen A, Yildiz G. Ultrasound Diagnosis of Traumatic Lens Dislocation. Journal of Emergency Medicine (0736-4679). 2013;44(1):e109-e110. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.077

Jarrett WH. Dislocation of the Lens: A Study of 166 Hospitalized Cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;78(3):289–296. doi:10.1001/archopht.1967.00980030291006

Lee S, Hayward A, Bellamkonda VR. Traumatic lens dislocation. Int J Emerg Med. 2015;8:16. Published 2015 May 27. doi:10.1186/s12245-015-0064-5