A Sizable Stone: Sonography in Sialolithiasis

CASE

An octogenarian gentleman with a history of atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and insulin-dependent diabetes presented to the emergency department with three weeks of pain and swelling near the right side of his face. He awoke that morning with a new symptom — difficulty swallowing, leading him to seek care in the emergency department. Associated symptoms included difficulty tolerating secretions, a change in tone of voice, and a dry cough. The patient was promptly evaluated in the critical care bay due to airway concerns.

He was tachypneic and sitting upright on the stretcher, spitting his secretions into a bedside container. His vital signs were otherwise unremarkable. There was no audible stridor. His exam revealed impressive right-sided tenderness and swelling involving his neck, submandibular soft tissue, tongue, and lower face. The overlying skin was without significant erythema and warmth, and no crepitus was appreciated. His oropharynx was clear with midline uvula and normal tonsils. He had no apparent periodontal lesions. Floor of the mouth was soft.

Labs demonstrated a normal complete blood count, and his metabolic panel was significant only for a creatinine of 2.5, consistent with his known chronic kidney disease.

A bedside flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy performed by the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) team revealed a widely patent airway with mild watery edema of the right arytenoid and pyriform sinus. They applied pressure to the submandibular area and noted purulence draining from Wharton’s duct on the right. A culture was obtained.

A bedside ultrasound and a CT scan were performed.

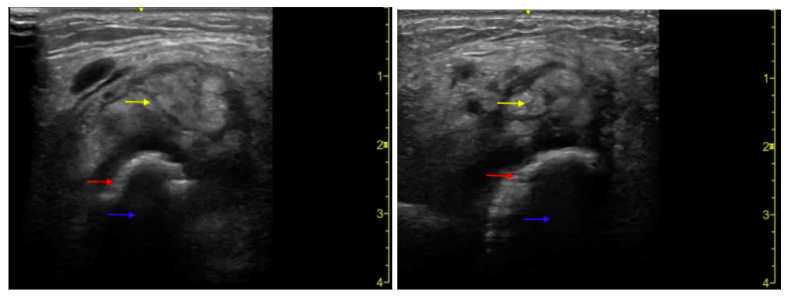

Ultrasound images demonstrate the submandibular gland (yellow). A hyperechoic stripe (red) with shadowing (blue) is seen in the far-field, consistent with sialolith.

Sialolith (red) visualized on non-contrast CT.

DIAGNOSIS

1.9 cm sialolith with associated sialadenitis of the right submandibular gland.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence and Demographics:

The estimated incidence of sialolithiasis ranges from 0.01% to 1% of the population, with males between the ages of 30 to 60 being the most commonly affected group. [1,2] It is very rarely seen in children.

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors:

The precise mechanisms leading to sialolith formation are unknown. Some postulate that microcalculi secreted by the salivary glands act as a nidus for stone formation, while others argue that oral flora or food debris within the salivary ducts are the likely culprits. [1] Additional factors such as increased viscosity of saliva, stasis of saliva, and inflammation likely all play some role. This is supported by the fact that nearly 90% of sialoliths occur in the submandibular gland, which produces a highly mucinous and viscous saliva that must then traverse an ascending outflow tract, increasing the likelihood of stasis. [1] Notably, patients with Sjogren’s syndrome more commonly experience sialolithiasis of the parotid gland. [3]

There does not appear to be any increased risk among individuals with high serum calcium levels, who live in an area with hard water, or those with a history of cholelithiasis or nephrolithiasis. [1,4,5] Smoking tobacco, dehydration and anticholinergic medication use may increase the risk, but definitive evidence is lacking. [1]

History & Physical:

Sialoliths cause localized pain in the area of a salivary gland. Non-obstructing stones may only be symptomatic during meal time, when there is increased saliva production and ductal peristalsis. Obstructing stones typically lead to inflammation, swelling and infection of the affected salivary gland, termed sialadenitis. Infections with S. aureus, S. viridans, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae are the most common. [2] These patients may report fevers, chills and a foul taste from the purulent drainage.

Physical exam findings include variable degrees of unilateral pain, swelling and erythema near a salivary gland. Sialoliths may be palpable or even visible during a careful oral examination, often spherical in shape with a yellow/white color. Fevers and/or purulence from the salivary ducts should also raise suspicion for sialadenitis.

Diagnostic tests in the ED:

Laboratory testing is non-specific, but should include blood counts to evaluate for leukocytosis. Serum amylase elevations are non-specific and have no reliable correlation with sialolithiasis.

The most frequently utilized imaging modalities for confirming suspected sialolithiasis are CT and ultrasound. CT scans are the current gold standard, with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 88%, respectively. [6] Studies evaluating the use of ultrasound have had variable results, with reported sensitivities ranging from 64-95% and specificities ranging from 80-97%. [6-8] Ultrasound sensitivity declines sharply for sialoliths <3mm in diameter. [7]

ED Management

Analgesia with anti-inflammatory agents or opioids should be provided. Antibiotics are indicated if fevers, leukocytosis or clinic signs of infection are present. Tintinalli’s recommends the use of cephalexin or clindamycin first-line. Emergency medicine providers may be able to expel a sialolith <5mm by using a combination of gentle massage, warm compresses, and sialogogues. ENT consultation is warranted for stones >5mm, as they often require specialized removal techniques. [1,2]

CASE RESOLUTION

The patient’s symptoms drastically improved with analgesia, IV fluids, and Unasyn. He also received three doses of Decadron for the impressive swelling. The culture obtained in the emergency department grew mixed flora and was felt to be nonspecific. He was discharged to home on hospital day 5 with a one week course of antibiotics and ENT follow up to remove the sialolith electively after the inflammation and infection resolve.

TAKE-AWAYS

Sialolithiasis is an uncommon and incompletely understood cause of facial pain and swelling.

Antibiotics are indicated in patients with signs/symptoms of infection.

Ultrasound is an appropriate first-line imaging modality, but it cannot reliably exclude sialolithiasis. CT remains the imaging gold-standard.

Conservative management may be appropriate for sialoliths <5mm; ENT consult is warranted for sialoliths >5mm.

Keywords: HEENT, ultrasound, sialolith

AUTHOR: Thomas Gomes, MD is a first-year emergency medicine resident at Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital

FACULTY REVIEWER: Kristin Dwyer, MD MPH, Assistant Professor Brown University, Director of Emergency Ultrasound Division, Director Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship.

REFERENCES:

Hammett J, Walker C. Sialolithiasis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549845/

Cydulka R, Fitch M, Joing S, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine Manual. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2018

Konstantinidis I, Paschaloudi S, Triaridis S, et al. Bilateral multiple sialolithiasis of the parotid gland in a patient with Sjögren's syndrome. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007;27(1):41-44.

Kim S, Kim H, Lim H, et al. Association between cholelithiasis and sialolithiasis: Two longitudinal follow-up studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(25):e16153.

Choi H, Bang W, Park B, et al. Lack of evidence that nephrolithiasis increases the risk of sialolithiasis: A longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196659.

Thomas W, Douglas J, Rassekh C. Accuracy of Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography in the Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Sialendoscopy for Sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(5):834-839.

Benito D, Badger C, Hoffman H, et al. Recommended Imaging for Salivary Gland Disorders. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. 2020;8:311-320.

Goncalves M, Schapher M, Iro H, et al. Value of Sonography in the Diagnosis of Sialolithiasis: Comparison With the Reference Standard of Direct Stone Identification. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(11):2227-2235.