Island Med: Challenges of Remote Healthcare

This post focuses on a resident's unique experience working during the summer months on Block Island, a small island off the coast of Rhode Island, and elaborates on topics and resources to consider if one is interested in practicing medicine in similar settings.

CASE

A 60-year-old man with a history of hypertension and smoking presents to the medical center with chest pain. Over the weekend, he developed chest pain while cleaning out his gutters that resolved with rest. This morning, he was working at his computer when he developed chest pain radiating to his left arm. It has since resolved, but he presents to the clinic for evaluation. An EKG obtained on arrival is unremarkable, but he soon develops chest pain again. A repeat EKG shows:

Image 1. EKG showing ST elevation in V2-V5 with reciprocal changes inferiorly.

DISCUSSION

What are your next steps?

This EKG shows a STEMI in V2-V5. Unfortunately, standard treatment options are limited as there is no cardiologist or catheterization lab available on the island. Understanding the history and geography of Block Island will illustrate the challenges of providing care in this setting.

Island Logistics:

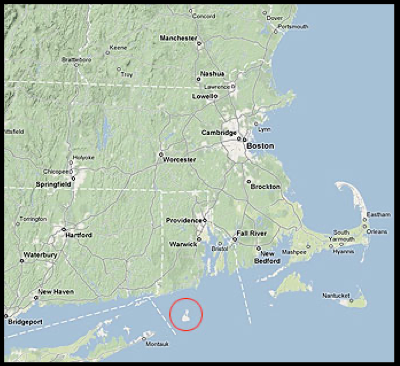

Geography:

Block Island is a small island located approximately 12 miles off the coast of Rhode Island. It is accessible via ferry from Point Judith, RI, Newport, RI, and New London, CT. It is also accessible via plane from Westerly, RI. The year round population is 1,010 according to the 2000 census though in the summer increases to 15,000 to 20,000 visitors daily [1]. The island is 7 x 3 miles and consists of 7,000 acres of land.[2] It is surrounded by beaches but contains 265 freshwater ponds and 32 miles of trails.[2,3] Much of the area has been preserved by local conservancies making it a popular and beautiful destination to visit.

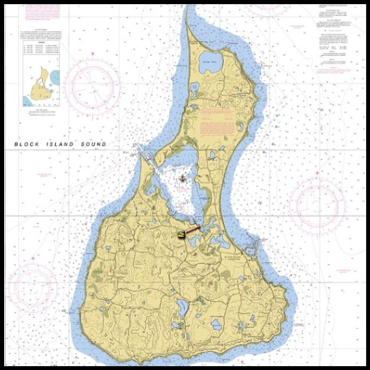

Image 2. Map of Block Island

Block Island is a small island off the coast of RI accessible via ferry or plane. [4]

History of the Island:

The island was originally inhabited by the Niantic people whose tribe eventually merged with the Narragansett people. They named it the ‘Island of Manisses’ meaning ‘Island of the Little God’.[4,5] During the 1500 and 1600s, the island was re-discovered by European settlers, including a Dutch Explorer ‘Adrian Block’, giving it the modern-day name of Block Island. It was later renamed ‘New Shoreham’ and was incorporated into the Rhode Island general assembly in 1672 [5]. Starting in the late 1800s, it gained the reputation as a popular summer destination for visitors from New York, Boston, and Providence.

Medical Care on the Island:

Until relatively recently, there was no centralized medical care on the island. Historians from the Block Island Historical Society note that island residents traveled to the mainland for care or received limited care from visiting nurses and doctors. Current day hotels such as ‘Spring House’ housed small offices for doctors. Mary Donnelly, known as the ‘island nurse’ provided medical care for over 50 years in the form of house visits. Her impressive work was documented in a short film titled “Island Nurse” [6]. In 1989, the Block Island Medical Center was founded with the goal of providing primary care for the island but also addressing urgent care and emergency needs [7]. With regard to the latter, the center works to facilitate “emergency air and marine transport of emergent patients to mainland receiving facilities” via collaboration with EMS, Coast Guard, and flight agencies [7].

The center is located up the hill from the town center and 10 minutes from the airport. It has several patient rooms and a resuscitation room with two beds. This room contains essential emergency medications and equipment such as: ACLS medications, a Zoll monitor, a BiPAP machine, a glidescope, direct and video laryngoscopy supplies, an EKG machine, splinting supplies, chest tubes, and an ultrasound. An x-ray machine is located in the neighboring room. No CT scanner is available on the island.

Transports:

The center is well equipped to service the primary and urgent care needs of the community as well as stabilize emergencies. However, most emergencies require transfer off island as advanced imaging, laboratory tests, and specialists are not available in real time on the island. Each transfer for a patient is unique as it is influenced by several factors such as weather, length of transport time, and acuity of condition. Understanding transportation systems and evacuation strategies is essential when practicing in any remote healthcare center.

Block Island does have a volunteer based EMS squad that was founded in 1950. It consists of approximately 21 volunteers, most of whom are BLS certified [8]. In winter months, calls may be as low as three per month, while in the summer calls may be upwards of 110. Volunteers often work additional jobs on the island, so it is common for them to have to leave work to respond particularly during summer months.

If a patient needs transport off island, there are several routes. One way off is via ferry, however this requires that an ambulance travels with a patient on the ferry during the one hour ride to the mainland. This is not ideal as it leaves the island without an EMS crew during that time. Additionally, once the ferry arrives on the mainland, additional transport time will be required to provide transport to the hospital. The drive is approximately one more hour to the nearest tertiary care center. A second option is fixed wing aircraft which allows for quicker transport time. However, accommodations must be made for transport to the island airport and at the arrival airport for patients to receive ground transport to the final destination. Helicopters are commonly used to fly the most critical emergencies due to their speed though can be limited by weather such as fog, which often affects the island. Finally, in dire circumstances the US coast guard can assist with transports, though this is also weather-dependent.

Image 3. Local volunteer EMS crew responds to a summer trauma on a main road.

Just how busy is the medical center?

In 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 4522 clinic visits. Between January and September 2021, clinic visits totaled 5460. This included a combination of primary care, urgent care, physical therapy, and nurse visits. Urgent care visits, which constitute a range of concerns such as chest pain, fish hook accidents, Lyme disease, and fractures peaked in August 2021 with 167 visits. It is interesting to note that scheduled medical visits totaled 301 visits during this month, requiring the clinic to accommodate a large volume of unscheduled visits. Trauma activations, typically requiring EMS activation, totaled at 78 activations by September for the 2021 year.

During the time period examined, 66 patients needed formal, organized transport off island. Each transport requires approximately 5 hours of work between direct patient care, stabilization of the patient for transport, and coordination with receiving and transporting facilities. The breakdown of transports was as follows: helicopter (25), fixed wing airplane (22), ferry (12), US coast Guard (6).

Figure 1: Medical Center urgent care visits from January to September 2021 peaked during the summer months.

Figure 2: Trauma rescue activations from January to September 2021 on Block Island peaked during June.

Case Resolution:

The case was discussed with the cardiologist at the nearest tertiary care center with PCI capabilities. TPA was considered due to concerns for prolonged transport time, however was unavailable on the island at this time. The patient was connected to the Zoll monitor and cardiac pads. He received 325 mg of aspirin, 1 mg/kg of lovenox based on medication availability, and 2 doses of sublingual nitroglycerin with good pain relief. He was transported by EMS to the island airport where he was transferred to a helicopter and flown to the tertiary care center without incident. He underwent cardiac catheterization and was successfully discharged from the hospital after a brief stay in the cardiac ICU.

So you want to work in a remote setting?

This case, while straightforward if presenting to a center with PCI capabilities, was made more complex due to limited resource capability and the need to transport a patient expeditiously off island. While studying the exact challenges of providing care in such settings can be difficult, case reports exist regarding unique cases such as providing care for an intubated patient on a resource poor island for greater than 24 hours or caring for cardiac arrests in locations such as Antarctica [9,10].

The American College of Physicians (ACEP) provides “HealthCare Guidelines for Cruise Ship Medicine” which outlines the medications recommended to have on board any ship. ACEP advocates for sufficient medications to care for two complex cardiopulmonary arrests, in addition to providing an extensive list of supplies to have on board [11]. Physicians can look to this for guidance when considering practicing in a remote location, as providing care aboard a ship is inevitably, ‘remote’ care.

Finally, for trainees, experiencing a rotation out of one’s comfort zone can be invaluable during residency. Surveys of medical residents rotating on rural Japanese islands found that much was gained by rotating in remote settings including learning to anticipate a patient’s worsening condition, collaborating with the community, and understanding the differences in capabilities between rural and tertiary care centers [12]. Seeking out a wilderness medicine elective or course in a unique setting or considering a wilderness medicine fellowship can be great ways to gain exposure to aspects of emergency medicine that may not be included in a standard curriculum such as the challenges of transport and how to recognize patients needing a higher level of care. Below is a list of resources that may be helpful in pursuing this interest.

● Wilderness Medical Society: https://wms.org/

● Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) Wilderness Medicine Fellowship Guide: https://www.emra.org/books/fellowship-guide-book/30-wilderness-medicine-fellowship/

● National Outdoor Leadership School: https://www.nols.edu/en/

AUTHOR: Christina Matulis, MD, is a fourth-year emergency medicine resident at Brown University/ Rhode island Hospital.

FACULTY REVIEWER: Heather Rybasack-Smith, MD, is an EMS trained attending physician at Rhode Island Hospital

REFERENCES

United Census Bureau. 2020 Census Results [Internet]. 2020. [Accessed Nov 2021]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/2020-census-results.html

The Nature Conservancy: places we protect, Block Island [Internet]. [Accessed Nov 2021]. Available from: https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/block-island/

Block Island Conservancy [Internet]. [Accessed Nov 2021). Available from: https://biconservancy.org/

Island History [Internet]. Block Island Info. [Accessed Nov 2021). Available from: https://www.blockislandinfo.com/island-information/history

Block Island Historical Center [Internet]. Block Island Timeline.[Accessed Nov 2021]. Available from: https://www.blockislandhistorical.org/block-island-timeline/

Tierney, Judy. “Island Nurse’ documentary about Mary D premieres.” The Block Island Times. April 10 2013. [Accessed Nov 2021] Available from: https://www.blockislandtimes.com/article/%E2%80%9Cisland-nurse%E2%80%9D-documentary-about-mary-d-premieres/32585

The Block Island Health Services [Internet]. [Accessed Nov 2021). Available from: www.bihealthservices.com

Rhode Island Department of Public Health [Internet]. Key determinants of rural health in Rhode Island. 2016. [Accessed Nov 2021). Available from: https://health.ri.gov/publications/databooks/2016KeyDeterminatesofRuralHealth.pdf

Ohta, R, Shimabukuro, A. Rural physicians’ scope of practice on remote islands: A case report of severe pneumonia that required overnight artifical airway management. J Rural Med, 2017; 12(1): 53-55. DOI: 10.2185/jrm.2925

Merefield, DC, Beckham, J (2016). Cardiac arrest - a successful outcome. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2017; 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taw015

American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policy [Internet]. Cruise ship health care guidelines. ACEP Clinical policies. 2018. [Accessed Nov 2021]. Available from: https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/preps/cruise-ship-health-care-guidelines---prep.pdf

Ohta, R, Son, D. What do medical residents learn on a rural Japanese island? Journal of Rural Medicine, 2018; 13(1) 11-17.. DOI: 10.2185/jrm.2950