A Case Of A Young Man With Extremity Paresthesias

CASE

A 29-year-old male with no significant past medical history presents to the emergency department for evaluation of progressive numbness and burning sensation to his bilateral hands and feet. He reports the symptoms have become so severe that he has started to have difficulty using his hands. He also states that he has had difficulty ambulating at times. He endorses neck pain and intermittently experiences a sensation that feels like “shocks down my spine” with movement of his neck. He has had poor PO intake related to recent homelessness. He has been living in his car while trying to find another apartment. He was bit by both a tick and a spider a few months ago and had transient elbow swelling after he noticed the bites. He also has had a dental abscess over the past few weeks which seems to be improving on its own. He denies fever, chills, night sweats, difficulty speaking, slurred speech or facial droop. All other ROS negative except as document above.

PMH: None known

PSH: Rotator cuff repair

Social Hx: recently living in his car, just found an apartment. Reports former tobacco use and IV drug use (heroin) but quit 2 years ago. Drinks alcohol twice monthly at parties. Smokes marijuana and uses whippets daily since age 16

Family Hx: No significant history of autoimmune, neurologic disease or cancer

Medications: none

Allergies: NKDA

Exam

Vitals: BP 137/88, HR 90, RR 18, SpO2 99% on room air, T 98.3 F

General: well developed, no acute distress

HEENT: small intra-oral abscess

Neck: supple, full ROM, no LAD

CV/Pulm: RRR, lungs clear, normal work of breathing

Abdomen: soft, NTND

Skin: warm and dry, small bite wound on L hand, other small wounds in various stages of healing on extremities

GU: normal rectal tone

Extremities: no joint effusion or tenderness, full ROM of all joints

Neuro: alert and oriented, speech fluent, no dysarthria, cranial nerves II-XII intact

Motor: 4/5 grip strength in UE b/l, 5/5 strength in b/l LE

Sensation: Diminished to finger tips and from calf to toes, worse progressing distally. Decreased vibratory sensation in b/l LE

Reflexes 3+ in lower extremities

Positive Romberg test

Wide based, ataxic gait

Laboratory testing shows:

WBC: 4.2, RBC: 4.0, Hgb: 11.1, Hct: 35, Plt: 281, MCV: 103

Na: 138, K: 4.0, Cl: 104, CO2: 26, BUN: 11, Cr: 0.79

AST: 23, ALT: 34, Alk Phos: 69, Albumin: 4.4, T. Bili: 0.6, D. Bili: 0.1

ESR: 10, CRP: 1.05

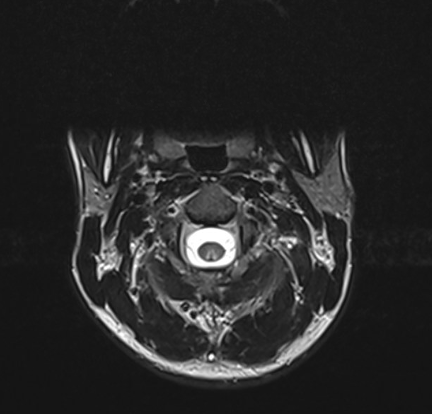

MRI imaging of the cervical spine shows:

Figure 1. MRI of c-spine

A final test was sent that clinches the diagnosis…

Vitamin B12 Level (ref 211 – 911 pg/mL): 200 pg/mL

DIAGNOSIS

Nitrous oxide induced vitamin B12 deficiency

DISCUSSION

Background

Nitrous oxide is used in many industries for various purposes. We are familiar with its use in medicine and dentistry as an induction agent for general anesthesia and procedural sedation. It is also used as an aerosol propellant in many household products such as Lysol, spray paint, and in whipped cream and as a fuel in motor racing. For many years, people have used nitrous oxide as a recreational drug, colloquially referred to as “huffing” or “whippets”. It is more commonly abused in the adolescent to young adult population. Typically, it is dispensed into a container such as a balloon and then inhaled, causing a high.

So, how is this related to vitamin B12 deficiency?

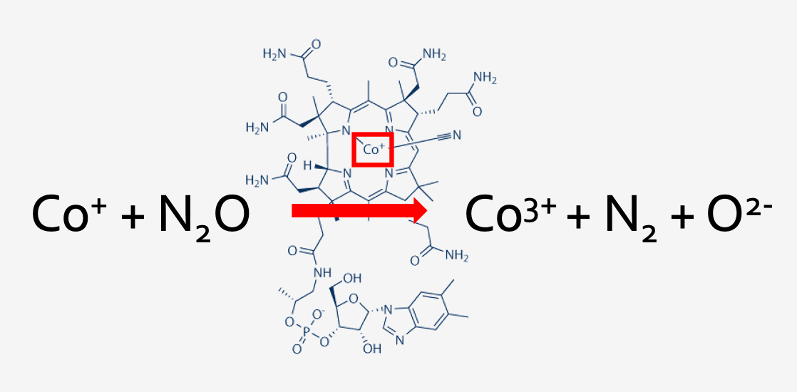

Figure 2. Oxidization of cobalt by nitrous oxide

The active form of vitamin B12 contains the element cobalt in its reduced form – Co+. When one inhales nitrous oxide, it oxidizes cobalt into Co3+ and Co2+ via an irreversible reaction, both of which render vitamin B12 inactive. This causes a functional vitamin B12 deficiency.

Vitamin B12 is an important cofactor in many of our body’s biochemical reactions, primarily for two enzymes:

A – methionine synthase: involved in the transmethylation of methyl tetrahydrofolate (MTHF) and homocysteine to methionine and tetrahydrofolate (THF), which is an important reaction in DNA synthesis and myelin synthesis

B – Methylmalonyl CoA-mutase: involved in the conversion of methylmalonyl CoA into succinyl CoA which enters the Krebs cycle and contributes to lipid and carbohydrate synthesis

Figure 3. Vitamin B12 as a cofactor

Without active B12, these important biochemical reactions are inhibited, leading to accumulation of methylmalonic acid and homocysteine. These substances can also be measured in the serum and help lead to a diagnosis of B12 deficiency.

Figure 4. Downstream effects of MMA and homocysteine build-up

In summary, vitamin B12 is an important cofactor for enzymes involved in reactions that maintain the integrity of the myelin sheath, protect nerves and contribute to DNA synthesis.

Signs/symptoms of B12 deficiency

Figure 5. Presentation of B12 deficiency

Most importantly, vitamin B12 deficiency can cause Subacute Combined Degeneration of the spinal cord because of its role in myelin sheath integrity and DNA synthesis. This can be both irreversible and progressive if the deficiency is not recognized and promptly corrected.

Figure 6. Posterior and lateral columns of the spinal cord

Degeneration occurs primarily in nerves in the dorsal and lateral columns of the spinal cord, which leads to impaired or loss of proprioception, vibration sense, tactile discrimination, paresthesias and burning pain, hyperreflexia, weakness, spasticity.

Risk factors for deficiency

- Nutritional deficiency – vegans, EtOH use disorder, developing countries

- Malabsorption – gastric surgery, pernicious anemia, gastritis, IBD, pancreatic disease

- Medications – gastric acid suppressants, metformin, nitrous oxide

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Vitamin B12 deficiency, leading to subacute combined degeneration, requires good clinical history and diagnosis.

Labs may show:

-Low or possibly low-normal Vitamin B12 levels

-Elevated methylmalonic acid and homocysteine levels

-Macrocytic anemia

MRI imaging may show:

-Symmetric T12 signal hyperintensity in dorsal columns

Differential diagnosis includes:

Copper deficiency, vitamin E deficiency, demyelinating myelopathies (transverse myelitis, MS), infectious myelopathy (HIV), neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis), peripheral polyneuropathy, methotrexate toxicity.

CASE RESOLUTION

Our patient was admitted to neurology and started on vitamin B12 supplementation, first parenterally and then oral supplementation daily. Addiction medicine was also consulted to help with counseling on cessation of nitrous oxide abuse.

TAKE-AWAYS

Keep this diagnosis in mind, especially when multiple risk factors are present

Neurologic damage from B12 deficiency can be progressive and permanent if not immediately corrected

Treat with B12 supplementation and address underlying cause

Author: Meredith Horton, MD is a fourth year emergency medicine resident at Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital.

Faculty Reviewer: Kristina McAteer, MD is an attending emergency medicine physician at Rhode Island Hospital and Newport Hospital.

REFERENCES

Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513. doi:10.1111/bjh.12959

Doran M, Rassam SS, Jones LM, Underhill S. Toxicity after intermittent inhalation of nitrous oxide for analgesia. BMJ. 2004;328(7452):1364-1365. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1364

Jordan JT, Weiser J, Van Ness PC. Unrecognized cobalamin deficiency, nitrous oxide, and reversible subacute combined degeneration. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4(4):358-361. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000014

Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):384-389.

Qudsiya Z, De Jesus O. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord. [Updated 2021 Jun 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.

Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2041-2042. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1304350

Stockton L, Simonsen C, Seago S. Nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017;30(2):171-172. doi:10.1080/08998280.2017.11929571

Yamada K, Shrier DA, Tanaka H, Numaguchi Y. A case of subacute combined degeneration: MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 1998;40(6):398-400. doi:10.1007/s002340050610