Brown Sound: Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection

CASE

A 60 year-old male with history of poorly controlled diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a prior MI presented as a transfer from an outside hospital for surgical management of suspected necrotizing fasciitis/Fournier’s gangrene. He reported symptoms of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and severe pain in the scrotum and perineum for several days. This began after he sustained a small cut to the area. He denied fevers, urinary discharge, respiratory symptoms, chest pain, but did endorse chills and night sweats.

On physical exam, the patient had erythema extending from his right buttock to his scrotum and the entire area was extremely tender to palpation.

Computer tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis at the outside hospital showed perianal subcutaneous gas in the right buttock, but the imaging did not fully evaluate the scrotum. Lab work was significant for a leukocytosis of 22.8. He was treated with pain control, clindamycin, Zosyn, and vancomycin at the outside hospital.

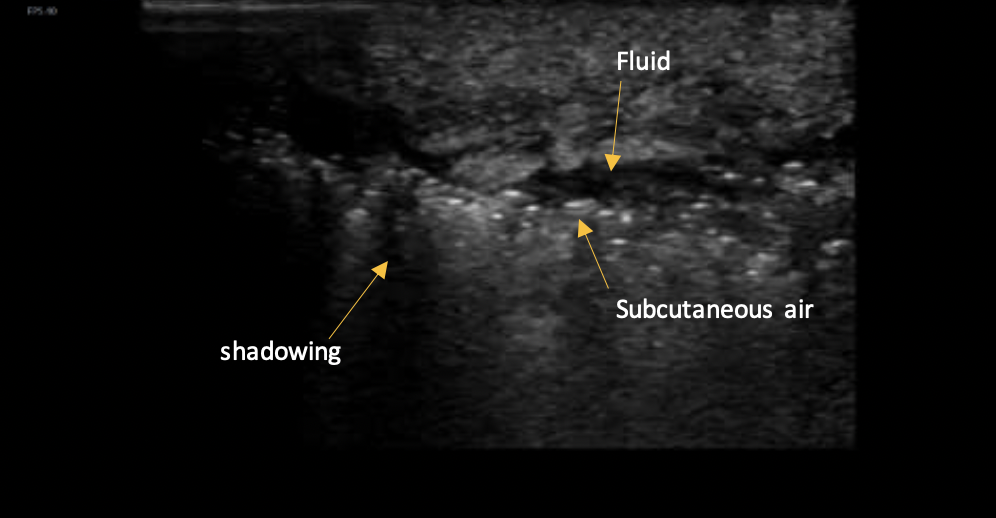

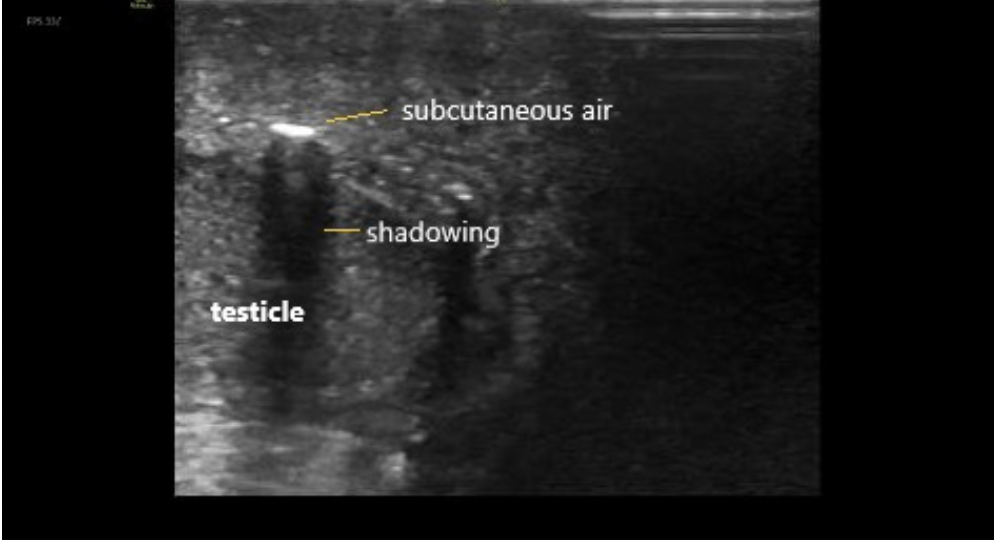

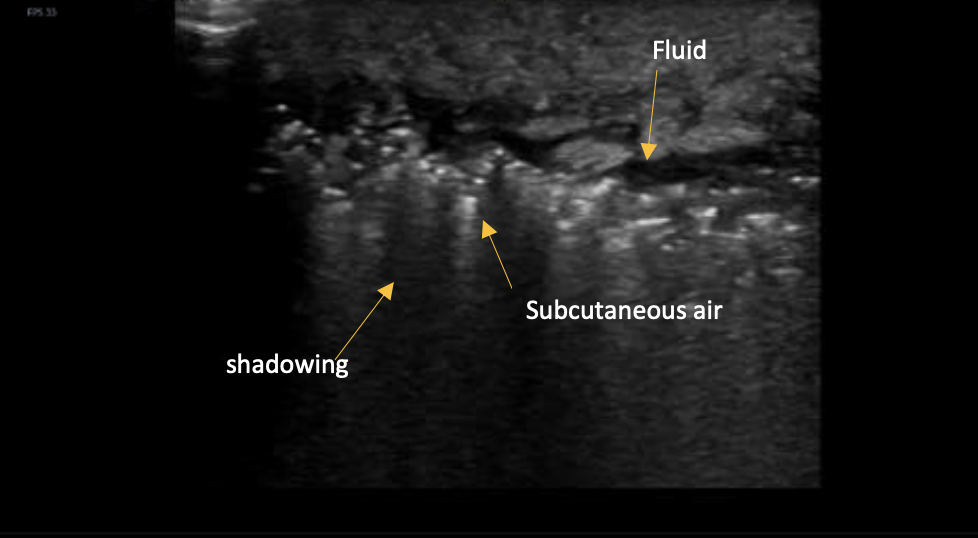

Because the CT did not extend distally enough to show the scrotum, point-of-care ultrasound was used to evaluate for the presence of subcutaneous air in the scrotum.

DISCUSSION

What is Fournier’s gangrene?

Fournier’s gangrene is a rapidly progressing necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) involving the perineal, perianal, and genital regions. It is a life-threatening condition that has a mortality rate of between 25-75%, depending on comorbidities and other clinical factors[1]. It is classically seen in men over 45, but can also occur in women. The infection usually starts as a simple abscess or minor infection, but quickly worsens, causing microthrombosis of the small subcutaneous vessels, leading to gangrene in the overlying skin. Patients with diabetes and alcohol abuse are at higher risk and the most significant predictors of death are age greater than 60 and complications during treatment[2].

Signs and symptoms

Patients may present with genital or perineal pain only. Lethargy and fever are possible, but not always present. Edema and erythema come later, with crepitus, ecchymosis, and bullous skin changes portending advanced disease. Early diagnosis is vital, as a delay in diagnosis increases tissue loss and leads to complications and higher rates of mortality.

Diagnosis by ultrasound

To diagnose a NSTI with US, first use a linear probe. When examining the area of interest perform the STAFF exam, which evaluates for subcutaneous thickening, air, and fascial fluid.

How do you differentiate this from cellulitis?

The early stages of NSTI can look clinically very similar to cellulitis, and cobblestoning will be present, but it is important to distinguish this diagnosis early as a delay in treatment significantly increases morbidity and mortality.

While the sensitivity of US has been reported to be as high as 88%, it is generally not used to rule out the diagnosis. However, with a specificity of 93% if findings are present it can significantly reduce time to definitive treatment.[4] While a CT may have better test characteristics, US offers the advantage of being fast, available at the bedside, and having no radiation.

The presence of subcutaneous air, which appears hyperechoic with shadowing underneath it, makes it very unlikely that what you are seeing is simple cellulitis. Accumulation of more than 2 mm of subcutaneous fluid is the most accurate diagnostic criteria on ultrasound to differentiate between NSTI and cellulitis.[5]

CASE RESOLUTION

This patient was evaluated by general surgery and urology in the emergency department and taken to the operating room for debridement of the entire area.

TAKE-AWAYS

Fournier’s gangrene is a rapidly progressing NSTI that has a high mortality rate.

Performing the STAFF exam with US can enable rapid diagnosis and treatment.

Accumulation of more than 2 mm of subcutaneous fluid is the most accurate diagnostic criteria on USto differentiate between NSTI and cellulitis.

Authors:

Hannah Chason, MD is a second-year emergency medicine resident at Brown University

Kristin Dwyer, MD is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and the Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship director at Brown University

REFERENCES

Zacharias N, Velmahos GC, Salama A, et al. Diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2010;145(5):452-455. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2010.50

Davis JE. Male Genital Problems. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, et al., eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1166534959.

Castleberg E, Jenson N, Dinh VA. Diagnosis of necrotizing faciitis with bedside ultrasound: The staff exam. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(1):111. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.8.18303

Yen ZS, Wang HP, Ma HM, Chen SC, Chen WJ. Ultrasonographic screening of clinically-suspected necrotizing fasciitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(12):1448-1451. doi:10.1197/aemj.9.12.1448

Lin CN, Hsiao CT, Chang CP, et al. The Relationship Between Fluid Accumulation in Ultrasonography and the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Necrotizing Fasciitis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45(7):1545-1550. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.02.027